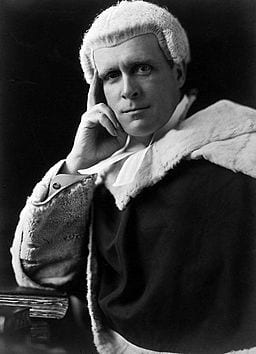

Looking for an article in the same volume of a journal, I stumbled upon this article, and it seemed worth reading and noting, for future legal historical thought. It is the text of a speech by Viscount (John) Sankey, delivered to an audience of historians, entitled ‘The Historian and the Lawyer: their aims and their methods’.[i]

Who was the author? Well, he is a familiar name to me from long-ago undergraduate legal studies, as a judge and Lord Chancellor of the past, and further details of his life (‘public’ school, university, prominence in the legal profession, politics, his long bachelor life and oddities, including something of a tendency to sulk and cry, in the face of professional setbacks, for example) can be found in the entry in the Oxford DNB.[ii]

He had studied history as well as law, and not long before this speech was published, he had made a very famous decision and pronouncement on burdens of proof in criminal law in Woolmington v. DPP (1935)[iii] – a case which required engagement with the law and legal writings of the past in some detail. Not a great deal of this comes through, however – and much of the material is more of a confident rehash of the sorts of material a reasonably well-informed general reader of his era, and with his schooling, might have known (see: tendency to equate history with war, and scattering of classical allusions).

He does note the existence of academic legal studies, and mentions Holdsworth and Maitland, but is really interested in the comparison between legal professionals and historians. Legal history seems to be an instrumental thing, rather than a pure academic pursuit:

‘one of the most important branches of history is history of the law itself, without which no lawyer’s knowledge can be really complete’ (97).

He presents some (rather banal) similarities and differences. Similarities include the idea that: both the lawyer and the historian are ‘taking part in an investigation of facts … to establish … truth’ (98);[iv] and also engaged in constructing a narrative (102); both are likely to have ‘stumbled into’ their profession, and to desire ‘the reputation which attends upon superior excellence’ in their chosen profession (98 – and note that everyone is assumed to be male); both have to find facts (99). Differences include the fact that historians tend to be looking at documents while lawyers have to deal with living people’s evidence (99).

There are a few random throw-aways which give a little insight into his attitude to the law of his own time. Litigants in person are ‘generally tiresome’ (100) for example. I am also intrigued by the way of thinking displayed in one of his more unusual flights of fancy, trying to imagine historians being more like lawyers,[v] suggesting that it might be worth trying to get at the historical truth around the Great War and its effects by having a rich American[vi] fund a collection of chapters by people from various countries involved/affected. This is conceived to be something along the lines of a jury (101). To be fair, he does not actually think it would produce a useful ‘verdict’. His view of both law and history is that they should eschew ‘partisanship’, but not ‘avoid the pull of personality’ (106 – great men then!).

It ends strongly (in my view), though, with a more interesting distinction between the importance of the influence of historical and legal endeavours, (noting that much damage can be done by blinkered, nationalist, interpretations of history, particularly since historians, unlike lawyers ‘address a jury of the young’ – 107) and, perhaps with a certain wistfulness, as he contemplated his recent demotion from the Woolsack, a final distinction between the historian, who ends his working life with the ‘friendship’ of the books he has written, and the lawyer who has no such companionship.

GS

21/10/2023

[i] History 21 (1936) 97-108.

[ii] R. Stevens. ‘Sankey, John Viscount Sankey, 1866-1948, lord chancellor’, ODNB online.

[iii] [1935] AC 462 – if you’ve studied criminal law, you know it … at 481: ‘Throughout the web of the English criminal law one golden thread is always to be seen, that is the duty of the prosecution to prove the prisoner’s guilt. No matter what the charge or where the trial, the principle that the prosecution must prove the guilt of the prisoner is part of the common law of England and no attempt to whittle it down can be entertained.’ Looking this case up, I was reminded (a) that it was tried (on one occasion) in Bristol and (b) that it was a wife murder case with a rather unconvincing-sounding defence. There was some appeal to historical legal texts in the case – and Sankey discussed these, Coke, Foster and Blackstone in particular: see 474 – 480. I was also surprised to see that it was not seen to merit its own chapter in P. Handler et al. (eds), Landmark Cases in Criminal Law (Hart, 2017). I see, though, that there is a very interesting recent treatment here: K. Crosby, “‘Well, the Burden Never Shifts, but It Does’: Celebrity, Property Offences and Judicial Innovation in Woolmington V DPP’ Legal Studies, 43: 1 (2023), 104–121.

[iv] Note the queasiness-inducing quotation about the search for truth, from Bacon’s ‘Essay of Truth’ which mentions the ‘wooing or love-making of it’, cited with apparent approval at 98.

[v] To me, it feels as if the energy is a little bit this.

[vi] Reference is made to Maecenas – look! I went to that sort of school – aren’t I great?!

Image: the man himself, smouldering to camera, if being slightly disrespectful to that law book under his elbow – I am, naturally, wondering what it is … c/o Wikimedia Commons.