On a previous stardate, back in 2020, I wrote a piece about a classic Star Trek episode, ‘Amok Time’ (1967). This is the one which features a trip to Vulcan, and Spock being on heat – due to the seven-yearly pon farr mating urge – and not even vaguely logical. Obviously, my inner legal historian (OK, not all that ‘inner’ …) was intrigued by the ‘trial by battle’ between Spock and Kirk over the minxy T’Pring (Spock’s fiancée, who was keen to dump him for a rather buffer Vulcan called Stonn). Now, in my continuing – possibly impossible – mission to watch everything Star Trek, I have seen a Voyager episode from 30 years afterwards, ‘Blood Fever’ (3:16, 1997), which takes up some of the threads from ‘Amok Time’, and expands upon some aspects of Vulcan mating and marriage customs, in the lore of the Star Trek universe. It also, perhaps, raises some questions about the pitfalls of trying to maintain storylines and ideas over a long period of time, when attitudes in our own world may have moved in important ways.

Anyway, the episode involves a male Vulcan engineering ensign, Vorik, going through the pon farr and focusing his attention on half-Klingon, half-human Lieutenant B’Elanna Torres. Vorik proposed to her (declares koon-ut-so-lik). She refused him, but he would not take ‘no’ for an answer and attacked her. She punched him out. However, the physical contact involved in their fight (he had her by the neck at one point, and held her face in a similar way to the famous ‘mind meld’ position) ‘infected’ her through sort of rapey telepathic bond, and Torres began to go into a version of the pon farr with Klingon characteristics. She still wasn’t attracted to Vorik, though, and pursued Lieut. Tom Paris, while they were stuck on a rather desolate planet, on an ‘away mission’.

The implications of the pon farr for those who could not get to Vulcan was explored. The deal with that is that, if they can’t mate or fight, or perhaps suppress the whole thing through meditation, a (male?) Vulcan may well die. So what to do? The whole problem is not helped by the Vulcans’ ‘Victorian’ attitude to the whole sex thing and insistence that the pon farr is terribly private. Vorik says insists that he can try and get on top of it, and ‘resolve [his] situation privately.’ Meditation is mentioned, but there is a strong hint at Vulcan wanking too (or is that just me?). Certainly wank-adjacent is the Doctor’s scheme of programming a Vulcan woman on the holodeck for Vorik.

The Vulcan is confined to his quarters – presumably justified on grounds of protection of the rest of the crew. He escapes, however, and follows Torres down to a planet where she is working, to ‘consummate their union’. It is not clear that her consent is in any way relevant to him. Seeing Torres and Tom Paris about to have sex, Vorik challenges Paris (the koon-ut-kal-if-fee). Torres steps in and takes the challenge and is allowed to do so. The two fight, Torres wins, and this purges both of them of blood fever.

What do we learn, in terms of law, customs and practice surrounding marriage and sex?

There is some expansion on the Vulcan trial by battle idea …

- It is possible for a woman to fight

- It can be fought without the ritual weapon, the lirpa

- Fighting itself gets rid of the pon farr chemicals

- Fighting need not be to the death, nor on Vulcan, to have this effect.

… and Vulcan marriage …

- Arranged marriages are the norm

- If it is logical to assume that one’s betrothed is lost, one may seek another mate

What do we learn about Star Trek and gender?

So – we are thirty years on from ‘Amok Time’: how has the mood changed with regard to ideas about gender and sex? Well, there are positive things: Torres is definitely her own woman, active, respected and brave, and she gets to participate directly in the ‘trial by battle’ section of the story, rather than sitting back decorously and letting the men fight it out. But there may be a bit too much emphasis on the nobility of Tom Paris, not wanting to have sex with B’Elanna while she is ‘under the influence’ – I mean, obviously this is good, but, dramatically, it is being set up as a balance to the attempted rape by Vorik on Torres, and the icky (at best) holodeck sexbot idea. And the joking discussions of Klingon ‘rough sex’ might not be beyond questioning.

I am left wondering about the choice to maintain, or bring back, the pon farr idea in the 1990s. I can see why it was tempting to bring in the conundrum of how to deal with desire in the situation of the long journey home of Voyager, but the (real) world changed quite a lot in those intervening years (challenges to and much removal of the marital rape exception, improvements in understanding of rape myths and gender inequality) and the narrative of virtually irresistible sexual urges in a male of a particular species (however muddied in gender terms by the transmission to Torres) might have been best left in Stardate 1967.

GS

17/6/2023

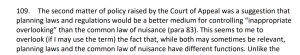

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons