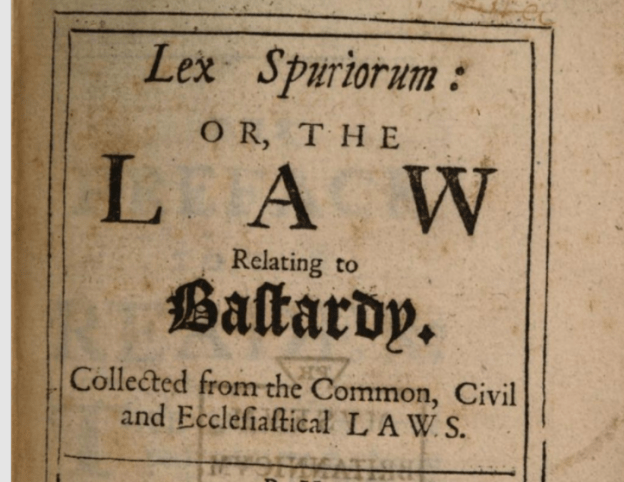

In the course of researching for a paper on how the law, over a long period of time, and in different jurisdictions, has handled scientific uncertainty with regard to the beginning of (legally valued/protected) life and paternity, I have become a little obsessed with an a little corner of family/succession law, that of ‘adulterine bastardy’. An ‘adulterine bastard’ was a child born to a married woman, but whose biological father was not (or was held not to be) the man married to the woman at the time of conception. Before the development of DNA testing, it was impossible to be sure on this matter, and before the development of blood testing – which could at least rule out some men as fathers – in the early 20th century, matters were even less certain. Central to the legal strategy found in several different legal systems, for dealing with such uncertainty, was some form of presumption that a child born to a married woman was the legitimate offspring of her husband, unless that was impossible. Impossibility became watered down over time in various ways, but I will not explore that here. What I will discuss is one aspect of this little niche area, and its potential impact and interest for wider areas of study. This aspect is the question of the upper limit for human gestation, and the exploration of this question in the Barony of Gardner case of 1824-5. An account of this case is easily accessible online, thanks to archive.org https://archive.org/details/reportproceedin00ofgoog/mode/2up and it seems to me a really interesting resource for teaching both Legal History and also areas such as gender and history, and the history of medicine.

The case concerned the right to a peerage – guess what, the Barony of Gardner. Can’t say I’ve ever heard of it – not one of the big ones, but there are those who value such baubles above and beyond the money and land, and that was all the more so a century ago.

The source, Denis Le Marchant, Report of the Proceedings of the House of Lords on the Claims to the Barony of Gardner (London, 1828), was written by a barrister – and it should be noted that he was not exactly a disinterested fan of obscure legal points, but counsel for one side in the case (the side of the petitioner, i.e. Alan Legge Gardner, apparently legitimate son of H and W2, in opposition to Henry Fenton Jadis/Gardner, who claimed to be the legitimate son of H and W1, but was, problematically, born after a long absence by H, which would mean that, for him to be legitimate, the pregnancy would have to have lasted 311 days). The case was heard in 1825 before a committee of the House of Lords.

There is quite a story – of foreign travel, adultery and apparently brazen lying. What I want to focus on, in particular, however, is the lengthy (though not complete) account of the examination of witnesses on the question of the possible length of gestation (and whether a gestation of 311 days was possible). This begins on p. 13.

There was a long list of medical men, variously described as physicians, surgeons, accoucheurs, and pairs of these titles. Some sported ‘M.D.’ labels, most did not. These are their names:

Charles Mansfield Clarke, accoucheur

Ralph Blegborough, M.D.

Robert Rainy Pennington, Esquire, accoucheur

Robert Gooch, M.D., accoucheur

David Davis, M.D.

Dr. Augustus Bozzi Granville, physician

Dr J. Conquest, physician

John Sabine, Esq. surgeon and accoucheur

Dr. Samuel Merriman physician and accoucheur

Dr. Henry Davis, physician

Dr. Richard Byam Denison,physician

Dr Edward James Hopkins accoucheur

Henry Singer Chinnocks, Esquire, surgeon and accoucheur

Dr. James Blundell, physician

Dr. John Power, physician accoucheur

After the ‘medical men’ had had their say, some women were allowed to speak, both in a ‘professional’ capacity, and also to give evidence as to their own experiences as to length of pregnancy. Mary Tungate. midwife was followed by the following women who had either experienced, or were experiencing, long pregnancies: Mary Wills, Mary Summers, Mrs. Mary Gandell, Isabella Leighton, Mary Parker, Mrs Sarah Mitchell. It is interesting to imagine the presence of these women, and especially pregnant Mary Parker, in the masculine environment of a House of Lords committee. I was interested to see that discussion relating to the midwife Mary Tungate seemed to assume that she was to be assimilated to a ‘medical man’ for the purposes of an exception to the rule against hearsay evidence: 170-1. The women were all deployed by the side wishing to show that it was not impossible that the child born after 311 days of absence was legitimate. It was admitted – 247 – that ‘they were not persons of high rank or distinction, — no one can think that such persons would expose themselves to a cross examination on the details of their pregnancy’. This does not seem very polite treatment for women who had submitted themselves to this ordeal.

The ‘medical men’ (and Tungate) were routinely asked the length of time they had spent in practice, the extent of their experience, their views of normal gestation periods, and the possibility of longer periods. Most answered around the 39-40 week mark here. Some cited instances of longer periods and thought the 311 day pregnancy a possibility, while others were quite sure that it was not. There were some interesting outlier views – including a late survival of the idea of differences relating to the sex of the foetus, with boys staying longer in the womb than girls – 152. Questions also demonstrated something of a lay obsession with the formation of nails as an indicator of gestational age – e.g. 15, 37.

There were some interesting exchanges on matters of authority (which was more important – the learning of well-known medical writers, or the experience of doctors themselves?) and of evidence – could the medical men use their notes (answer – this seems to have been allowed, if they were in their own writing and contemporaneous, as an aide-memoire: see, e.g., 60, 66, 119, 136. The meticulous note-taker, Dr Granville, in the end had some of his patients brought in, so as to circumvent objections that this was not the best, or legitimate, evidence – 87]

There were also some slight episodes of sparring about confidentiality – it is interesting to see ideas of patient confidentiality at this early stage – see, e.g., 66, 133. This concern about confidentiality apparently did not apply to the wives of the medical men themselves – two of these women were given as examples of women who had had long pregnancies – 67, 111 – (and appear to have kept period diaries – I remember being told this was a good idea, in the excruciating one-off assembly on this topic given at my school – obviously the reason was to be ready for possible evidence before a House of Lords committee…).

[Should you be interested in the result, Alan Legge Gardner won, and became Third Baron Gardner. Honour and bloodlines prevailed. Or something. That seems of considerably lesser interest than the enquiry itself, which seems to have been on a fairly large scale, and to have shown some interesting differences of professional opinion in this still-early period of formalisation of medical training and expertise. I am still working on how it fits into a longer story of uncertainty in this aspect of ‘the secrets of women’, which remained officially mysterious, and open to some very odd theories and evidence, into the twentieth century].

GS

30/11/2020

Updates:

NB – the Gardner/Jadis case was mentioned in a ‘Who Do You Think You Are’ investigation on Frances de la Tour: Frances De La Tour – Who Do You Think You Are – Society scandals, an illegitimate child, and a landmark divorce… (thegenealogist.co.uk)

By the evil magic of the internet, I have been linked up to this – Isabel Davis, The Experimental Conception Hospital: Dating Pregnancy and the Gothic Imagination, Social History of Medicine, Volume 32, Issue 4, November 2019, Pages 773–798, https://doi.org/10.1093/shm/hky005 – dealing with disturbingly rapey 19th C sci-fi writing sparked off by the Gardner case. What an interesting article (and especially the Gothicism and balloon-related bits). Law, sci-fi and Gothicism (and a couple of well-judged points about the limitations of the blessed Foucault): if it could just include a vampire or two, it would tick all of my boxes.