Part I[1]

George R.R. Martin’s (unfinished) Song of Ice and Fire series, also, as Game of Thrones, a massively successful TV series, is set in a quasi-medieval fantasy world. I am happy to note that there is quite a bit of legal content, with references to trials, laws, lawmakers. It falls within the Venn diagram overlap of my interests (fantasy, medieval history, law), and so naturally I have been making notes on the legal or legal-historical ideas present in the series. Because of the incomplete nature of the SIF cycle, it is not possible to draw a definitive picture of the prevailing legal system(s), but there are several points of interest which I will set out here.

I: LEGAL SYSTEM(S)

- Law-making

Sources of law appear to include custom (which varies according to territory and lordship) and deliberate law-making.

Kings have the right and obligation to pass laws, though some had little enthusiasm for the role. Robert Baratheon complains that ‘Laws are a tedious business’ (though at least he found them preferable to ‘counting coppers’).[2] The king’s second-in-command, the Hand of the King, is involved in drafting laws.[3] In the brief reign of Joffrey, the king at times made decrees and the Small Council gave their assent,[4] though it is unclear whether they were more than a rubber stamp, and whether an un-approved decree would be valid.

Kings of old had not necessarily wished to impose one set of laws on the Seven Kingdoms, King Aegon leaving matters to ‘the vagaries of local tradition and custom’, but King Jaehaerys, his grandson, ‘created the first unified code, so that from the North to the Dornish Marches, the realm shared a single rule of law’.[5] ‘Top-down’ provision of laws was, thus, possible and accepted. Such laws survive their maker, but may be unmade. Thus, laws of King Maegor had prohibited the Faith from bearing arms, but Cersei suggested ‘undoing’ these three-hundred-year-old laws, allowing the ‘Sparrows’ to defend themselves.[6] Similarly, Princess Arianne of Dorne argued that rules barring those of the Kingsguard from marriage, which had been made by Aegon the Dragon, could be revoked –

‘What one king does another can undo or change’[7]

backing up this proposition with the argument that Joffrey had changed the rules regarding the Kingsguard, in that they had formerly served for life, but he had dismissed Ser Barristan Selmy while still alive.

Monarchs in SIF vary in their enthusiasm for law-making. Daenerys Targaryen has an interventionist instinct. Some of her efforts to change practice with regard to personal freedom will be considered in Part II. She also wished to change the dress code in Meereen, banning the status-emphasising tokar. an extremely impractical garment, but is dissuaded from this course of action because it would be extremely unpopular.[8] She shows a desire to use law to improve her people’s morals, though this is tinged with awareness that she cannot go too far too fast without endangering her achievements. Of her partial victory with regard to the fighting pits of Meereen (see Part II) she says

‘Perhaps I cannot make my people good,… but I should at least try to make them a little less bad’.[9]

She has, it would seem, made a study of the laws prevailing in Meereen, and decided that few of them are good, though she is keen to continue those few good laws from the previous regime which she finds (e.g. the rule that dead arena beasts are to be used for stew for the poor).[10]

A slightly more participatory process of law-making can be seen in the attempt to fix the rules of succession to the Iron Throne, in the Great Council held in 101 AC,[11] though how binding such determinations were appears to have been contested: certainly, a subsequent king, Viserys I, did not consider himself bound by the rules of that body,[12] though others fought a civil war to enforce it.

- Lands without lawyers?

A striking feature of Westeros is the complete absence of a legal profession: we see neither trial lawyers nor professional judges nor draftsmen. Although there are individuals who devote themselves to learning – the maesters in Oldtown,[13] and some princes[14] – and there are accepted legal procedures, individuals do not have legal representation, and nor is there any sign of specialised scholars of jurisprudence, though there is mention of what might be a legal historical work: Justice and Injustice in the North: Judgments of Three Stark Lords, by Maester Egbert.[15] Unsurprisingly, given the lack of a legal profession, there does not seem to be anything approaching a ‘writ system’, and legal matters are brought before kings by petition.[16]

Kings on the Iron Throne have an official called the ‘master of laws’ (e.g. Ser Kevan Lannister is noted as master of laws in King Tommen’s small council,[17] and Aegon the Conqueror had a ‘master of laws’),[18] but these are noble ‘civil servants’ rather than trained jurists (or holders of a postgraduate degree in law), and their duties are unclear. Of the official called the justiciar, we know little (and less), other than that during Cersei’s regency, it is held by Lord Merryweather.[19] The official called the King’s Justice (Ser Ilyn Payne) is simply an executioner,[20] with additional charge of dungeons and gaolers.[21]

- Jurisdiction

Kings on the Iron Throne do justice (‘criminal’ and ‘civil’) though others (particularly the Hand of the King) might do this when the king is unavailable or unwilling.[22] Eddard Stark takes a very royalist view of the constitution, stating that ‘all justice flows from the king’.[23] Those aspiring to a royal role are expected to do justice to their people. Daenerys Targaryen devotes considerable time to providing decisions on petitions – including legal matters – brought to her by the people of Meereen.[24] In her view, ‘Justice … [is] what kings are for.’[25]

The usual legal business dealt with by Ned Stark as Hand is described as ‘hearing petitions, settling disputes between rival holdfasts, and adjudicating the placement of boundary stones’, but he also heard complaints concerning a knight’s attacks on various holdfasts].[26] The Hand’s judgments might be overruled by the king, thus when Tywin Lannister adjudicated a border dispute between two houses over a mill, Aerys II overruled him and awarded the property to the side which lost at first instance.[27]

Lords appear to have jurisdiction both as lords, with respect to their own rights, and as representatives of royal justice. For example, we see Lord Randyll Tarly sitting in judgment in the fishmarket at Maidenpool, presumably as royal representative, with Lord Mooton, the territorial lord.[28] Some claim rights of summary execution, as can be seen in Roose Bolton’s hanging of a miller who married without Bolton’s permission or knowledge.[29]

An exchange between Maester Pycelle and Ned Stark shows disagreement as to the relationship between the jurisdiction of royal and lordly authorities. A complaint of the rampages of Ser Gregor Clegane having been made to the Iron Throne, Pycelle says that the appropriate recipient of the complaint is not the king but Clegane’s liege lord: ‘These crimes are no concern of the throne. Let them seek Lord Tywin’s justice’. Ned Stark sees things differently, however, stating that ‘It is all the King’s justice …North, south, east or west, all we do we do in Robert’s name.’[30]

There were some disputes about jurisdictional issues between the Iron Throne and the Faith in the time of King Jaehaerys, but these were brought to an end by the king swearing that the Iron Throne would always defend the Faith.[31] It is not clear, however, exactly how the two jurisdictions were seen to relate thereafter. The High Septon during Cersei’s regency says that Jaehaerys the Conciliator ‘deprived [the Faith] of the scales of judgment’.[32] He claims jurisdiction over adultery and sexual offences, and homicide (or deicide – see Part II) of the previous High Septon, and treason, and accepts that the Faith does not have the right to impose capital punishment.[33] Where there is overlapping jurisdiction, the accused seems to be able to elect the forum. Thus, Cersei is afforded the option of letting the Faith sit in judgment on her or having a trial by battle according to royal justice.[34]

Prior to the Conquest, individual territories had their own processes of law-making and administration, aspects of which continued to echo during the post-Conquest period, though there is little information on this. We know, for example, that in the past, each of the Iron Islands had a ‘rock king’ who dispensed justice, made laws and settled disputes,[35] and that decrees altering the law were made in Dorne.[36] As will be explored in Part II, at least some territories are allowed to retain their laws or customs in some particular areas of law.

Some groups purport to try criminals, though their right so to do would no doubt be disputed by the Iron Throne. For example, Beric Dondarrion’s brotherhood try the Hound, Sandor Clegane, for crimes including murder,[37] and had tried the Brave Companions/Bloody Mummers for various killings and rapes, and Septon Utt for killing boys he molested.[38]

Some areas do not accept the idea of law at all (or are thought not to do so). Samwell Tarly notes that ‘There are no laws beyond the Wall’,[39] and is horrified that Craster is said to ‘obey no laws but those he makes himself’.[40] Jon is not surprised that the people of Westeros consider the wildings ‘scarcely human’, explicitly because of their lack of laws. He notes that

‘They have no laws, no honour, not even simple decency. They steal endlessly from each other, breed like beasts, prefer rape to marriage, and fill the world with baseborn children’ ,

but he grew fond of them, and even respected some of them and some of their views.[41] The wildings saw their lack of respect for authority and law as a positive thing, and contrasted themselves – the ‘free folk’ – with the ‘kneelers’ of Westeros.

With multiple jurisdictions, it is not surprising to see disputes as to which should apply. The television series[42] has Viserys Targaryen end up badly, crowned with molten gold and dying as a result, because he broke a Dothraki rule against carrying blades in their holy city, though he did not accept that their law applied to him.[43]

- Justice and vengeance

There are interesting parallels to early medieval moves from family-based ‘feuding’ responses to misconduct, to central, ‘justice’ responses in exchanges between Eddard Stark and those offended by the activities of the brutal Gregor Clegane. Ned will not give permission for vengeance, but only justice according to law.[44]

- Form of trial

Litigation is not the only method of dealing with legal disputes: mediation is mentioned, in a property case (dispute over possession of a cavern), in the Dawn Age.[45] Also, lords may have the power to sentence without trial those caught red-handed, as in the case of Will, a poacher who had taken the black after being caught by Mallister freeriders skinning a deer in the Mallisters’ own woods. He had done this rather than having his hand removed, indicating that they had, or assumed, the right to punish.[46] Nevertheless, court proceedings are noted on several occasions, allowing us to see something of ideas of procedure and proof in different jurisdictions.

There are accounts of lords doing justice. For example, we see Lord Randyll Tarly sitting in judgment in the fishmarket at Maidenpool, with Lord Mooton, the territorial lord.[47] Tarly is described sitting on a specially erected platform, near a long gallows which could accommodate twenty men. Mutilatory and capital sentences are passed and carried out immediately, and some corpses are left hanging for some time.[48] Matters which were regarded as offences included theft from a sept, food adulteration, passing on sexually transmitted diseases and assault with a knife.[49] The cases are to be tried over more than one day, and those accused of crimes are kept in a dungeon pending trial.[50]

There is a form of ‘ecclesiastical court’, at least for those who follow ‘the Faith’ of the seven gods. At times, there is a jurisdictional overlap between royal justice and ‘ecclesiastical’ justice, as where Cersei and Margaery are accused of offences which are contrary to secular and religious law (sexual treason, and, in Cersei’s case, homicide of sacred individuals – the High Septon and the King). Cersei has the option of letting the Faith sit in judgment on her or having a (secular) trial by battle. She decides to opt for the latter, as she has few friends among the Faith.[51] Margaery, however, chooses to be tried by the Faith.

‘Royal’ trials are held in public. At least in treason trials, there are three judges, and there is some religious participation – so that, in Tyrion’s trial for the regicidal poisoning of Joffrey, the proceedings commence with a prayer by the High Septon, asking the Father to guide them to justice.[52] The accused is asked whether he is guilty.[53] The judges ask questions of the accused.[54] Witnesses for the prosecution are heard first, then those for the defence, if available. The accused may not to speak without leave of the court, and does not seem to be able to cross-examine witnesses against him.[55]Trial by battle is a possible mode of proof, at the election of the accused (and Tyrion Lannister selects this proof).[56] The accused may (or must? this is not clear) have a champion rather than fighting in person, thus in the case concerning Tyrion’s alleged killing of Joffrey, Oberyn of Dorne fights for him.[57] A champion is also assigned to fight ‘for the deceased’ – in this case, Gregor Clegane fights ‘for Joffrey’,[58] demonstrating, incidentally, that these proceedings are understood as more of an appeal or private prosecution than a ‘state’ prosecution. Tyrion had previously insisted on trial by combat, ‘judgment by the gods’, also with a champion, when accused of the attempted murder of Brandon Stark.[59] Certain individuals are constrained in their choice of champion. Queens must be defended by a sworn knight of the Kingsguard, which may be inconvenient.[60]

Joffrey insists on a trial by combat, to the death, in a land dispute between two knights (the fight being ordered to be in person rather than with champions. Such a mode of trial in a land case seems to be illegitimate,[61] though it is an interesting echo of the early use of trial by battle in the writ of right in common law.

Ideas of ‘due process’ may be seen in Tyrion’s objection to being confined in the Eyrie without trial, and insisting on a trial according to the king’s justice.[62] We see little of ‘pre-trial procedure’, or detection, though torture is not entirely unknown. Thus, after terrorist murders in Meereen, Daenerys approves ‘sharp’ questioning of suspects (i.e. torture).[63] Cersei Lannister goes further, and has her sadistic assistant, torture ‘The Blue Bard’ to obtain a (false) confession of having had sex with Queen Margaery,[64] also lying and saying that if the confession is made, the bard will be allowed to take the black.

Less obviously showing ideas of due process is the fact that not all ‘royal’ judgments were preceded by a trial. Thus, Ned Stark sentences Gregor Clegane to death for killings, rapes and destruction on the basis of accusations, with no trial, also stripping him of rank, titles, lands, incomes and holdings.[65] Likewise questionable from this perspective is the fact that there does not seem to be an age-qualification for judges: thus, it is suggested that Tyrion should be tried before Robert Arryn, a pettish and unstable young boy.[66] Nor is there, apparently, an objection to a judge on the ground that he is related to the accused, for, when Tyrion is tried for the killing of Joffrey by poison, the judges are Oberyn of Dorne, Mace Tyrell and Tyrion’s own father, Tywin Lannister.[67]

At a lower level, trials may be brief or non-existent. In the judicial session of Lord Randyll Tarly, at Maidenpool, mentioned above,[68] trials or disposals are very brief. Some, such as that in which a prostitute is accused of spreading ‘the pox’ seem simply to be accusations, without argument. In other cases, the lord’s common sense or feeling for the guilt or innocence of those before him seems to be the decisive factor.[69]

‘Ecclesiastical’ courts, in the Faith, use a court of seven judges. There are three women, representing the maiden, mother and crone, and presumably four men representing the other gods or aspects of God.[70] The Faith may torture potential witnesses, e.g. by whipping Osney Kettleblack to ‘find the truth’ of accusations of sexual misconduct against Queen Margaery when the High Septon was suspicious of his (made-up) confession of involvement.[71] It may also attempt to coerce a confession from a suspect by harsh imprisonment, as in the case of Queen Cersei, accused of adultery, fornication and arranging the murder of a High Septon: she was taken, imprisoned in the sept, and ‘encouraged to confess by hourly visits of a septa’.[72]

Even some outside the law employ a degree of formal procedure. Beric Dondarrion demonstrates that he is not a bandit and is not engaged in lynching by his insistence on trying those accused of crimes, rather than simply killing them.[73] When he and his brotherhood try the Hound, Sandor Clegane, for crimes including murder,[74] the trial has elements of informality, with several people, including a young girl and an old woman, bringing accusations and the Hound answering back, defending himself.[75] Beric will not make a summary judgment, saying that ‘You stand accused of murder, but no one here knows the truth or falsehood of the charge, so it is not for us to judge you’. He says that judgment must be by ‘the Lord of Light’ and so there must be a trial by battle.’[76] In this case, however, there is no champion – the Hound fights in person (unlike Tyrion, he is well-equipped to do so]. Beric is his opponent. The combat is unarmoured, the Hound being allowed his shield and a sword, while Beric has a shield and a flaming sword. The priest Thoros leads those present in prayer to the Lord of Light before the battle, asking him ‘to show the truth or falseness of this man’.[77] When the Hound wins, the result is respected, and he is allowed to go.

- Kings, queens and the law

There is no Magna Carta or other document or principle explicitly holding monarchs to the law. Varys notes that one view of kingly power is that it derives from the law, but that there are other views – that it comes from the gods, or from the (possibly malleable) belief of the people.[78] It is certainly the case that some monarchs flouted the rules which applied to others. As Catelyn Stark notes in the context of incest, though this was an offence ‘hated by gods and men’, ‘Like their dragons, the Targaryens answered to neither gods nor men’.[79] It is arguable that this breaking of the rules enhanced the reputation of house Targaryen as special, set apart for kingship – or even semi-divine. Jaime Lannister dreams of wedding Cersei and marrying Joffrey to Myrcella, showing everyone that ‘the Lannisters are above their laws, like gods and Targaryens’.[80] Less image-enhancing, at least after his demise, was the conduct of ‘Mad’ Aerys Targaryen who ignored all rules of due process, killing and torturing many subjects.

Concluding thoughts on law in general

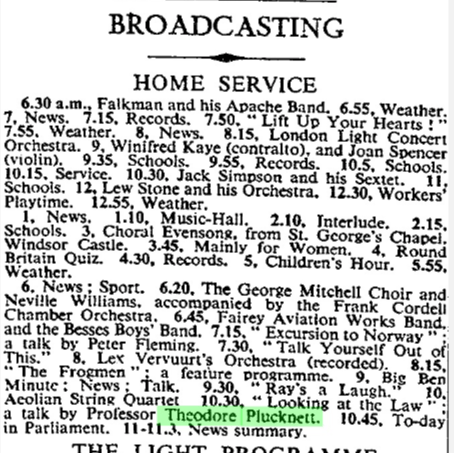

The Seven Kingdoms and the Iron Throne clearly demonstrate the existence of ideas of law and justice, though there is little explicit discussion of the content of these ideas. A difference is made by Ned Stark, as Hand, between justice and vengeance,[81] and, as we have seen, there are some safeguards for accused persons, though torture is seen, and there are cases of condemnation without trial. Daenerys Targaryen is particularly keen to ‘do justice’, and examines her own conduct to ensure that it has been just – for example, questioning herself about the display of punishment and exhibition of the dead in Meereen after it is captured, comparing herself to the slavers of Astapor, but concluding that, unlike them, she had imposed punishment on those who ‘deserved it’, and telling herself that ‘Harsh justice is still justice’.[82] Stannis Baratheon has a less questioning approach, content to take a literal and strict view of law: His harsh and unyielding view of law is shown in his statement that ‘Laws should be made of iron, not of pudding’,[83] and his treatment of Davos (later Ser Davos Seaworth)- mutilating his hand for smuggling despite ‘the Onion Knight’ having saved his life.[84] His brother, Robert I Baratheon, however, had been known for mercy contrary to the strict letter of the law.[85] The delightful Joffrey portrays mercy as a feminine weakness, and vows that during his reign, the full punishment would always be exacted (at least for treason).[86] This echoes the religious idea of the Faith that justice is for the Father and mercy for the Mother.[87] There are certainly resonances with medieval ideas of mercy, and intercession, as particularly feminine.

Part II: SUBSTANTIVE LAW

- Persons

Slavery, freedom and points between

Personal freedom – or its absence – is a recurring theme in SIF and GOT. Different territories have different attitudes to, and laws concerning, slavery: this is a particular concern of Daenerys Targaryen in her progress through various lands outside Westeros. Slavery is lawful in some realms and groups, such as Astapor, Volantis, and amongst the Dothraki.

Where slavery persists, enslaved people are essentially chattels,[88] and can be ‘bought and sold, whipped and branded, used for the carnal pleasure of their owners, bred to make more slaves’.[89] They are inherited when their master dies, unless explicitly freed.[90] Manumission appears to be possible, particularly on death of the owner, but the process is not described. The enslaved can also buy their own freedom, which suggests that they are able to amass savings, rather than paying all incoming money over to their masters.[91]

There is a variety of standards of treatment for the enslaved. Some – such as the Unsullied – are mutilated, and may be made to kill and die for their masters. It is noted that the slaves of Volantis are assigned to a role – sweeping up dung, acting as prostitutes, fighting or other functions – and are tattooed to indicate this role.[92] Dothraki and some others oblige the enslaved to wear collars, presumably to mark their status.[93] Ancillary laws are necessary to safeguard the institution – so in Volantis, it is forbidden to help a slave escape.[94]

Slavery is not permitted in Braavos, a state founded by escaped slaves,[95] nor in the Seven Kingdoms of Westeros.[96] A major feature of the progress of Daenerys Targaryen is her strong opposition to slavery, and her freeing of the enslaved wherever possible. Victarion Greyjoy also frees galley slaves, modelling himself on Daenerys.[97]

So important a principle is the outlawry of slavery in Braavos that it is regarded as the First Law of Braavos that ‘no man, woman or child in Braavos should ever be a slave, a thrall or a bondsman’, and this rule is engraved on a prominent arch.[98] Slavery is described by those of Westeros as an evil, and an ‘abomination’ to all of the gods of the Seven Kingdoms,[99] and Ser Jorah Mornomt’s selling of some poachers to a Tyroshi slaver instead of giving them to the Night’s Watch’ was regarded as a capital offence.[100] The instinct that people cannot be owned, and are not chattels, is demonstrated nicely in the television series, in a conversation between Jon Snow and Samwell Tarly: Snow tells Tarly that they can’t steal Gilly, the young wife of the repellent Craster, and Tarly responds ‘We can’t steal her. She’s a person, not a goat.’[101]

Pentos does not maintain with any great enthusiasm the ban on slavery which it was forced by the Braavosi to enact.[102] So, for example, those who were enslaved elsewhere seem to remain slaves there,[103] and although they are not technically slaves, there are those who are very close to such a status, so Magister Illyrio Mopatis tells Tyrion that his house servants will not refuse him sexual service, and makes it clear that he sees captives as the chattels of a captor.[104]

A state of servitude which falls short of full chattel-slavery is traditional to the Iron Islands. The Ironborn use some captured on raids as thralls, to do things considered beneath the Ironborn themselves, in particular mining.[105] While the life of a thrall is very difficult, this does not amount to slavery, since the thrall is regarded as a man, not a chattel, and may not be bought and sold. Although the thrall owes his captor service and obedience, he may hold property, and may marry a spouse of his choice. What is more, the children of such a union would be regarded as free and Ironborn.[106] Some rulers of the Iron Islands disapproved of thraldom and sought to end the status,[107] but it was allowed by Balon Greyjoy, and so is legal at the time of the Song cycle.[108]

Those who free the enslaved find themselves having to deal with the aftermath of abolishing the institution. They may offer compensation for the damage caused by escaping slaves. For example, the Iron Bank of Braavos compensated the successors of former slave-owners for the ships seized and sailed away by the original escaping slaves more than a century beforehand, though they would not restore the value of the slaves themselves.[109]

Daenerys Targaryen faces claims by former slave owners, who have been, or say they have been, damaged by the process of abolition. A boy attempting to claim for offences of murder and rape by his family’s former slaves against his father, brother and mother, during the rising which led to the overthrow of Meereen and the abolition of slavery there, is sent away without the sentence of hanging which he had desired for the former slaves. Daenerys rejects his claim both because she had pardoned all crimes committed during the sack of the city, and also because she will not punish slaves ‘for rising up against their masters’.[110]

Some claims are for economic loss. A nobleman of Meereen, Grazdan zo Galare, makes a claim for a share in the profits of weaving done by his former slaves. These women had been taught the skill by another of his slaves, a woman now dead, whose name he was not able to remember. The nobleman’s claim is, however, unsuccessful, since it was the old woman, rather than the ex-master, who had taught them to weave. In addition, the noblemen is ordered to buy the women an expensive loom, as a punishment for forgetting the name of the old woman.[111]

Daenerys is faced with the problem of retroactivity, and, whether as a matter of law or policy, decides that slave owners cannot be punished for conduct which, prior to the abolition of slavery in Meereen, was regarded as legitimate. So, when an ex-slave accuses a nobleman of rape for his actions towards the ex-slave’s wife, formerly the noble’s (enslaved) ‘bedwarmer’, the noble having ‘taken her maidenhood, used her for his pleasure, and gotten her with child’, this is unsuccessful. The ruling is that, at the time when the noble had sex with the ‘bedwarmer’, she was ‘his property, to do with as he would’, so that ‘By law, there was no rape’. The claimant does, however, obtain money to pay for ‘raising the noble’s bastard as his own’.[112]

Daenerys finds it impossible to maintain her absolute anti-slavery stance, due to political opposition. A peace deal struck between her city of Meereen and Yunka’i meant the partial acceptance of slavery. If a slave was brought into her realm by a Yunkish owner, he did not thus become free. This was the price she had to pay for the Yunkish promise to ‘respect the rights and liberties of the former slaves [she] had freed.[113]

In addition, she is faced with the situation of some noble Meereenese wanting to sell themselves into slavery, because their lives have become squalid, and they think that they will be better off as slaves in the Free Cities: an interesting problem of present free will versus anti-slavery absolutism. In the end, she decides that she cannot or will not stop this, as long as it is actually voluntary: thus, ‘[a]ny man who wishes to sell himself into slavery may do so. Or woman.’ … But they may not sell their children, nor a man his wife’.[114] Having accepted that such transactions are allowed, she imposes a tax on them.[115]

Her freeing of the slaves of Astapor does not lead to a no-slavery area there either, since, once she has left, slavery is restored, albeit with a reversal in those who were masters and those who were slaves.[116]

The issue of slavery in the Song of Ice and Fire is particularly interesting because characters (and particularly Daenerys Targaryen) have to negotiate a world in which the issue is contested, with contrasting rules and views in different countries. In many ways, the issues and views are more reminiscent of those prompted by African slavery in the New World, rather than medieval slavery. While there were strong voices condemning slavery in the medieval period (e.g. St Wulfstan), Daenerys’s attitude – and her solutions – are rather more post-Enlightenment.

Marriage

Marriage is important in Westeros, as it was in medieval Europe, for the regularisation of sexual conduct and the orderly transmission of property. In the world of Song of Ice and Fire, marriage laws and customs differ on religious, cultural and territorial lines.

In ‘the Faith’, (the ‘new’ religion of seven gods, or a seven-fold God), marriage must be between one man and one woman.[117] This also appears to be the case in those following the way of the Old Gods of the North and those following R’hilor, Lord of Light. Not everyone has always stuck to the monogamous model, however. Some Targaryens took more than one wife and while the Ironborn have only one ‘rock wife’ at home, they are allowed as many ‘salt wives’ as they can capture and keep.[118] Despite attempts to outlaw the practice of taking these additional, captured, wives,[119] the Ironborn maintain it at the time of the Song cycle. The Dothraki seem to allow at least khals more than one wife, and amongst traditionalist Dothraki, the khal’s bloodriders share his wives.[120]

Marrying close family members is regarded as wrong (‘seen as a sin by the Faith’, ‘hated by the gods’ and ‘a monstrous sin to both old gods and new’ by most in Westeros, but the Targaryens frequently married siblings or other close kin, sometimes justifying this as necessary to keep pure ‘the blood of the dragon’.[121] Rather more Egyptian than medieval. The twins Cersei and Jaime Lannister also have a long term incestuous relationship, but keep it secret,[122] though Jaime dreams of marrying Cersei, and also marrying their children to each other.[123]

Marriage is prohibited to the Kingsguard and the Night’s Watch, to silent sisters and septons and septas. and the maesters also are celibate.[124] At least for a man of the Night’s Watch, marriage could lead to capital punishment,[125] though less permanent breaches of the oath of celibacy are not taken very seriously (Jon Snow notes that men of the Night’s Watch visiting prostitutes ‘was oathbreaking too, yet no one seemed to care’,[126] and Dareon does not regard visiting prostitutes or undertaking a one night ‘marriage’ to a prostitute as serious or dangerous breaches of his oath.[127]

There appear to be at least social conventions concerning the requisite age or level of maturity for completion of the marriage. Thus, when Robert Baratheon proposes that Sansa Stark and his heir, Joffrey, are betrothed, Sansa is eleven and Joffrey twelve. He says that the actual marriage ‘can wait a few years’.[128] Tyrion proposes that Myrcella weds Trystane Martell of Dorne when she reaches her fourteenth year.[129] Menstruation rather than a set age seems to be enough to make a girl old enough for marriage. Magister Illyrio noting that Daenerys Targaryen ‘has had her blood. She is old enough for the khal’.[130] We might note that the age of Daenerys when married was adjusted in GOT: the actress Emilia Clarke was well over the age at which modern audiences would consider her capable of consent to sex and marriage, or, indeed to being stripped and pawed by less-naked males.[131]

One marriage which does not seem to fit the pattern of is pattern is that of the baby heiress Lady Ermesande Hayford to Cersei Lannister’s thirteen-year-old cousin, Tyrek (a match motivated by a wish to obtain the child’s lands).[132] This appears to be regarded as a full marriage rather than a mere betrothal, despite the bride’s tender age and presumed lack of consummation. Perhaps it is technically a betrothal, or open to disavowal when she reaches majority, though practically and politically, such a disavowal would be extremely unlikely (In the event, Tyrek disappears, presumed dead, so the point is moot).

Marriage may involve two stages – the contract or betrothal, which may be revoked, though it is considered binding in honour, and the final marriage.[133] A royal betrothal or marriage contract is considered void, and vows are cancelled, according to the Faith if the bride’s family are involved in treason against the groom, as is alleged against the Starks by Joffrey and his supporters.[134]

The marriage ceremony itself, in the Faith, involves the making of vows before witnesses, in the presence of a septon, and symbolic removal of a ‘maiden’s cloak’ (with her father’s sigil or colours) from the woman, and its replacement with the bride’s cloak (featuring her husband’s emblems), demonstrating her move from her father’s protection to that of her husband.[135] All very ‘coverture’. Consummation is also necessary, and might be preceded by the bawdy ‘bedding’ custom, which functions as confirmation that bride and groom at least had the opportunity and capacity to consummate. There may also be the exhibition of sheets after the wedding night, as an additional confirmation that the marriage has been consummated. In at least some traditions, a strong sense of unity of persons is expressed in the marriage ritual. For example, the marriage of Alys Karstark and Magnar of Thenn, according to the R’hilor rite, involves jumping a ditch, and the idea that ‘Two went into the flames’ ‘one emerges’ is expressed. Furthermore, the repetition of ‘What fire joins, none may put asunder’ is obviously similar to Christian rites.[136]

The people of Westeros adhere to different religions, and marriage rites vary. Generally, there do not seem to be arguments as to whether a marriage conducted according to one rite is regarded as valid by the adherents of other religions. Some may choose to make sure that there will be no problem by holding a double ceremony, in both godswood (for the Old Gods) and sept (for the Seven or New Gods).[137] There may be problems of ‘conflict of laws’ with regard to more foreign traditions, however. Thus, a Westeosi rite marriage would not be recognised in Meereen – unless Daenerys Targaryen marries Hizdahr according to the rites prevailing in Meereen, they will not be regarded as being lawfully married, so that any children they have will be illegitimate.[138] Since Daenerys more or less complies with this, one must conclude that she assumes this ‘foreign’ marriage would be seen as valid in Westeros.

Marriage may be arranged, and strong pressure may be brought to bear, but some form of consent is necessary. Daenerys does not want to marry Drogo, initially, but her brother Viserys orders her that she will.[139] She ‘consents’ to sex (and therefore ‘completes’ the marriage) with Drogo on their wedding night (it is presented in this way, though there is so much mention of fear that one must presume that a low threshold was being employed).[140] Similarly, even a marriage forced upon a vulnerable woman, with the threat of violence and mistreatment, might be regarded as not sufficiently outrageous as to be impossible to maintain Thus, ‘the Bastard of Bolton’ forced Lady Hornwood to say her vows to him in appropriate form, in order to acquire her land, later starving her to death. A maester pronounced that ‘Vows made at swordpoint are not valid’, but it is thought that the Boltons would be unlikely to accept the invalidity of this marriage which brought them valuable lands.[141] We might see this as entirely about having the power to disregard the law, but perhaps it imports an idea of at least arguable validity. The wildings’ custom of bride-stealing was not seen as excluding consent.[142] The stealing was, rather, a way of showing stealth and bravery, such as a wilding woman might be thought to admire.

At least in the upper echelons of Westeros society, lords have a role and a responsibility with regard to female tenants. A liege lord has a duty to find a suitable husband for widowed female tenants.[143] This right or responsibility may be politically useful. Theon Greyjoy, for example, speaks of making a marriage alliance using his sister, Asha [II:350]. The right may be used vindictively, as when Joffrey and Cersei arrange a marriage between Tyrion and Sansa Stark. Joffrey has this right because Sansa is a royal ward, and her brother – who would otherwise have the right – has been attainted a traitor.[144] The right is not available to those below the rank of lord: thus a castellan cannot make marriage pacts.[145]

As was the case in medieval Europe, marriages can, on certain, restricted, grounds, be ‘undone’ (which seems to mean that, as with divorce a vinculo matrimonii, it was as if it had never happened). The marriage of Tyrion Lannister and the peasant girl or ‘whore’, Tysha, for example, was ‘undone’ at the behest of his father Tywin, (perhaps on the ground that it had been entered into through deception),[146] and a marriage not consummated – such as Tyrion’s marriage to Sansa Stark – can be set aside ‘by the High Septon or a Council of Faith’.[147]

Once married, Westerosi husbands have considerable control over their wives’ person and property. They can chastise an adulterous wife.[148] Again, though, this was not uncontested. Dorne, influenced by the rules of the Rhoynar, did not allow husbands to chastise wives in this way.[149] According to a decree from the reign of Gaemon Palehair, ‘husbands who beat their wives should themselves be beaten, irrespective of what the wives had done to warrant such chastisement’.[150]

Even in mainstream Westeros, there are limits. In particular, the chastising husband was restricted in that he must use ‘a rod no thicker than a thumb’ – an echo of the post-medieval distortion of common law spousal chastisement limitations known as the ‘rule of thumb’.[151] And Queen Rhaenys Targaryen, doing justice in the absence of King Aegon, whilst accepting that ‘the gods make women to be dutiful to their husbands’, so that it was lawful for them to be beaten, decided that the number of blows should be limited to six (representing each of the gods, save the Stranger, who was Death).[152] In a case in which a man had beaten his wife to death, she judged that the blows exceeding six had been unlawful, so that the brothers of the dead woman could ‘match those blows upon the husband’.[153]

It appears that the law in Westeros includes something along the lines of common law coverture, since Daenerys notes (implicitly as a difference’ that ‘in Qarth man and woman each retain their own property after they are wed’.[154] She discovers, however that they also have a ‘custom that on the day of union, a wife may ask a token of love from her husband and the husband from the wife’ – these ‘requests’ not being amenable to denial [ibid.] Also suggesting the husband’s power over property brought to the marriage by the wife is the description of the Boltons using a (forced) marriage as a way of acquiring immediate rights in the wife’s lands.[155]

Mayhem, disfigurement, deformity

Possibly not fitting in entirely snugly at this point in my framework, but important to note nonetheless is the frequent mention of the bodily damage and/or disfigurement of various people.

Sometimes injuries are defined as ‘maims’ – a concept well-known to scholars of medieval law, and still retaining some role in law today (I am working on this at the moment). At other times injury or disability or disfigurement is mentioned in a way that is not particularly ‘legal’, but is, nevertheless, noteworthy, in terms the attitudes, either of the characters or society in this imaginary world. At times, it may also relate to the assumed attitudes of readers or viewers of these works.

As will be mentioned below, the law of Westeros, and its practice, included mutilatory punishments for a variety of offences – as did several medieval western European jurisdictions. Davos Seaworth and Jaime Lannister both have a body part deliberately removed: fingers in the case of Davos and a hand in the case of Jaime. (The latter was not a punishment, however.) Both of these are injuries which would, in medieval England, have counted as mayhem). Similar in some ways, though not the result of human agency, is the episode in which the Greatjon, having been rowdy with Robb Stark, has two fingers bitten off by Grey Wind the direwolf.[156]

The importance of a hand, and especially a sword hand, is emphasised by Jaime Lannister, who identifies himself very strongly with this particular body part: ‘I was that hand’.[157]

Some hope is held out for the ‘maimed’: prosthetic hands do not seem to be out of the question,[158] and some ‘maimed’ men are nevertheless effective warriors.[159]

Sticking with mayhem for a moment, there are also some suggestions of consented-to body alteration which would have amounted to mayhem in medieval English law, at least if inflicted by another: the practice of the mountain clan, the Burned Men, was to self-injure ‘to prove their courage’. This might involve removing a nipple or an ear (not mayhem) a finger or an eye (potentially mayhem).[160]

Several characters are in some way damaged or disfigured. How are they treated? At times, the answer is ‘questionably’. A particular example is the frequent repetition of the fact that (in addition to his short stature) Tyrion Lannister has ‘mismatched’ eyes which people find unsettling.[161] This could be passed off as representing the prejudiced view of that world, but it is repeated so frequently, and by the omniscient narrator as well as individuals, that that would be fairly weak pleading. It does link to a depressingly pervasive tendency to see eye abnormalities as especially indicative of something in the nature of moral shortcoming: the windows to the soul and all that. Want an obvious villain? Give them non-standard eyes. Never doesn’t hurt. Adding an extra layer, it should be noted that this was something removed from the television series, though it could easily have been done with coloured contact lenses: whether in belated recognition of its lazy unkindness or because of an assumption that TV audiences would be too unsettled by ‘mismatched eyes’ is not clear.

‘Cripple’ is used frequently in relation to Bran,[162] and there is an idea in the world of the Song that euthanasia might be a good option, if one is very disabled. Thus, Jaime thinks Ned should end Bran’s torment, as a ‘mercy’: ‘’Even if the boy does live, he will be a cripple. Worse than a cripple, a grotesque. Give me a good clean death’.[163] (Tyrion, however, disagrees). Interesting echoes of some modern debates on quality of life and euthanasia there.

B: Criminal Law

The Song of Ice and Fire mentions a variety of different ‘criminal’ offences, many of which are broadly similar to (medieval) English offences (pleas of the crown), though often there is insufficient evidence to allow exploration of the definition of the individual crime. There are offences against the person, against property and the state or crown.

Treason

Treason is a recognised concept, though, as in medieval Europe, its definition appears somewhat uncertain or contested. It includes at least killing the king and adultery by or with the queen.[164] Those in power might try to extend the concept, thus Cersei Lannister states that saying that Joffrey is not the true heir to Robert Baratheon is treason and Joffrey says failure by those instructed to swear fealty to him to do so is treason.[165] Ultra-loyalist Eddard Stark considers it treason not to reveal that Joffrey is not the son of Robert Baratheon, and so is not the true heir to the Iron Throne. Littlefinger, however, taking a more pragmatic approach, says it is only treason ‘if we lose’.[166]

A glimpse into (at least popular understanding of) the law of treason by adultery can be seen in the statement of Lancel Lannister to his cousin Jaime, that while he had had sex with Cersei, he was not a traitor because he had withdrawn before emission, and ‘It is not treason unless you finish inside’.[167] Clearly, then, assuming that such withdrawal is seen as a reliable method of contraception, Lancel understands the treasonous element of this version of the offence to be activity which would endanger the purity of the royal line, rather than any sort of sexual activity with the queen.

A treason conviction in Westeros leads to forfeiture of land and titles, as in medieval England. The effects thus stretch beyond the perpetrator himself or herself.[168] Women and children connected with rebellious males can be adjudged traitors, suggesting, perhaps, an idea of treason by contagion, or at least, in the case of children, a low threshold for capacity for guilty intention.[169] Joffrey, as king, calls a woman a traitor, and has her locked up, when she comes to his court and asks for the head of an executed traitor whom she loved, as she wants to ensure that he has proper burial. The royal logic is that ‘If you loved a traitor, you must be a traitor too’.[170] The context, however, indicates that Joffrey is not acting in accordance with law or custom in his determinations.

There is, perhaps, a wider idea of offences of ‘lesser’ treason, or sedition, lurking in the popular understanding. Jaime Lannister notes that the ‘old penalty for striking one of the blood royal’ was losing a hand’.[171] This suggests that action short of ‘high’ treason, and extending beyond the persons of the king, queen, heir and heir’s wife, could be taken particularly seriously. Also, those who disparage those in power may face disabling punishment. So a tavern singer who made a song that ridiculed the late King Robert, and Queen Cersei, is subject to mutilation.[172] Cersei also presses for mutilation of anyone speaking of incest or calling Joffrey a bastard, though this is not accepted by others.[173]

Somewhat akin to treason is the offence of ‘deicide’ with which the High Septon wants to try Cersei Lannister. Killing the High Septon (or complicity in his homicide) is so regarded because the person in this role ‘speaks on earth for the gods’.[174]

An interesting idea which may be from a different legal tradition is that desiring the queen can be treason. Daenerys tells her lover, Daario, that once she is married (to Hizdahr) ‘it will be high treason to desire me’ – this, presumably reflects the law of Meereen law.[175] One wonders about detection of an offence of this sort, in the mind of the desirer.

Desertion from the Night’s Watch

This appears to be an offence with no possibility of defence. ‘The Law is the Law’, Ned Stark says of the deserter he executes in the first episode of the TV series, and neither he nor the deserter himself regard fleeing from ‘the Others’ as excusing behaviour.

Homicide

Killing another subject other than in war or in execution of justice is a crime, and is designated murder. A more expansive view of the conduct which can amount to murder is taken than would be found in the medieval common law – thus, not feeding one’s wife might be regarded as murder.[176] It is seen as a plausible defence to a murder charge that one was acting on the orders of a superior: e.g. when Beric Dondarrion’s brotherhood try the Hound, Sandor Clegane, for crimes including murder,[177] the Hound denies guilt, and says, in relation to the accusation that he murdered the butcher’s boy, Mycah, that he ‘was Joffrey’s sworn shield. The butcher’s boy attacked a prince of the blood’, and when Arya Stark says it was she who attacked Joffrey, the Hound argues that he ‘heard it from the royal lips. It’s not my place to question princes’.[178] This defence does not, however, convince his accusers (though, as he is successful in a trial by combat under the auspices of R’hilor, the Lord of Light, perhaps there is some approbation of his argument).

Vengeance is not regarded as an excuse or justification for homicide, so Robb Stark executes Rickard Karstark for his vengeance killing of two Lannister prisoners.[179] Likewise, being ‘mad with love’ is not an excuse (or not a complete excuse?) for homicide.[180]

There is room for differing views on the borderline between killing made lawful by war and murder. Thus Eddard Stark regarded as murder the killing of Prince Rhaegar Targaryen’s wife and children, during the war which led to the defeat and deposition of the Targaryens by Robert Baratheon, but Robert regarded it as legitimate action during a time of war, however troubling (and, initially at least, ordered the killing of Daenerys Targaryen and her unborn heir once he heard that she was pregnant).[181]

In Westeros, tournaments may end in death, without condemnation of the killer, and at Dothraki weddings, fights to the death over women are unpunished.[182] Beyond Westeros, some cultures enjoy homicide as a spectacle, akin to Roman gladiatorial games. This is not acceptable to (at least some) Westerosi sensibilities. Thus, Daenerys Targaryen bans the fighting pits of Meereen. She is, however, obliged to reopen them, to ensure political stability. There is pressure both from the populace who wish to watch ‘the mortal art’, and the fighters who want the chance to fight for glory.[183] She tries to make these arenas less offensive and cruel than they had been, insisting that fighters must choose freely to participate, or else be in certain classes of criminal (murderers and rapers may be forced to fight, as may slavers, but not thieves or debtors) and all fighters must be of age.[184] She does not manage to do away with the ‘humorous’ fights of ‘cripples’ and dwarfs.

Particularly condemned are the kingslayer, the kinslayer and the killer in violation of guest-right.[185] Violations of guest-right, , under which it was forbidden to kill one who had eaten at one’s board, and for the guest to kill his host, are condemned particularly amongst the Northmen,[186] but guest right is mentioned in relation to widely spread parts of Westeros, for example: the Wall, the wildings and the North , Dorne.[187] There is a suggestion that it is a matter of the laws both of gods (old and new) and of men.[188] Kinslaying is likewise described as an offence against the laws of gods and men.[189]

There is some idea of sacred spaces in which special rules of peace apply. Bloodshed is forbidden in Vaes Dothrak, the sacred city of the Dothraki.[190] Nevertheless, there is a loophole, and traders there employ stranglers to kill thieves, so as to kill without offending against the ban,[191] and Khal Drogo kills Viserys without offending against the ban by crowning him with molten gold.[192] Places sacred to the Faith are also not to be used for bloodshed. The High Septon regards the beheading of Eddard Stark on the steps of the Great Sept of Baelor as a profanation.[193]

Interestingly, and unlike the situation under the laws in medieval Europe, there is no suggestion that suicide is regarded as a crime. Shara Dayne’s suicide is seen as something to pity rather than to condemn.[194] The supposed suicide of Ser Cortnay Penrose is not particularly condemned.[195] Tyrion considers killing himself with poisonous mushrooms, rather than allowing Cersei to capture him alive,[196] and although that does not prove that suicide would not be condemned, there is no sense that he has moral reservations about it.

Cannibalism, whether or not involving homicide, however, is a capital offence, at least under Stannis Baratheon’s rule, and even if the person in question is starving.[197] The Dothraki clearly did not consider that any laws forbade leaving ‘deformed children’ to be eaten by feral dogs.[198] How Daenerys’s smothering of the living but incapable Khal Drogo would be viewed in Dothraki or Westerosi law is unclear.[199] She clearly saw it as a mercy-killing, and the right thing to do. Euthanasia is a contested issue, but there is some support for it. It is suggested that Bran should be put out of his misery after his fall and paralysis, and that Patchface the fool should be given milk of the poppy as a method of euthanasia when he has lost his mind, but these options are not taken up,[200] and Val, the ‘wilding princess’ advocates killing children with greyscale – smothering, stabbing or poisoning them.[201] Beric Dondarrion, Sandor Clegane and others approve of giving the dying (after a fight) ‘the gift of mercy’.[202] The House of Black and White in Braavos (in which Arya Stark ends up) also gives out the ‘gift of mercy’ or ‘gift of who shall live and who shall die [which ] belongs to Him of Many Faces’.[203]

Whether or not abortion is an offence is unclear. Lysa Arryn and Littlefinger’s baby was aborted, Lysa being tricked by her father into drinking an abortifacient,[204] but, although the dying Hoster Tully feels guilt, it is not clear whether this would be regarded as a crime. Cersei also admits to having aborted Robert Baratheon’s child: ‘My brother found a woman to cleanse me …’.[205] North of the Wall, abortion is not seen as a big deal, and it is the choice of the pregnant woman. Thus, when Jon Snow is reluctant to have sex with Ygritte, Tormund does not see the problem: ‘if Ygritte does not want a child, she wil go to some woods witch and drink a cup of moon tea’.[206] Similarly in the Iron Islands, ‘moon tea’ is used: Asha Greyjoy also consulted a ‘woods witch’ to learn how to make this, ‘to keep her belly flat’ after starting to have sex.[207]

Sexual offences

Rape is certainly a criminal offence, but it is widely practised.

It is unsurprising in a patriarchal, quasi-medieval world to see at least some men of Westeros blaming women for their own rape, if they act outside certain norms. So Lord Randall Tarly tells Brienne of Tarth that she will have ‘earned it’ if she is raped, because of her ‘folly’ of taking arms and acting as a knight. If she is raped, he tells her not to look to him for justice.[208] He had made a similar statement in the past, when a group of knights had had a bet as to who could take Brienne’s ‘maidenhood’. Tarly thought they would have taken her by force eventually, but he laid the blame for the knights’ conduct squarely upon Brienne: ‘Your being here encouraged them. If a woman will behave like a camp follower, she cannot object to being treated like one…’.[209] Jokes and bawdy stories about non-consensual sex were also current,[210] and it is regarded as plausible that women make false claims of rape.[211]

The description of bawdy stories concerning Lann, trickster ancestor of the Lannisters, which have him ‘stealing in night after night to have his way with the Casterly maidens whilst they sleep’ do not use the word ‘rape’ about this conduct, and it seems unlikely that it would be so regarded in the world of the Song.[212]

Rape is regarded as normal after a battle victory, though Daenerys Targaryen is unhappy with this practice, and tries to rein in the Dothraki when they behave in this way.[213] Stannis Baratheon actually manages to keep his soldiers in check during the fighting in the North, and it is remarked that only three wilding women were raped after his victory.[214]

It is accepted, even by the ‘abolitionist’ Daenerys Targaryen, that a master having sex with his slave does not commit rape, because the slave is his property.[215]

Signs of changes over time and different views on the relevance of women’s consent to sex can be seen in discussions of the ‘right of the First Night’ (an echo, of course of the fictitious right associated with real ‘feudal’ societies – and seen, e.g. in the historically questionable film Braveheart). This seems to have been present in at least some parts of Westeros, was valued by ‘many lords’ and was banned by King Jaehaerys I Targaryen, at the behest of his sister/wife.[216] Even at the time of the Song cycle, however, some lords maintain the right. Roose Bolton states that ‘where the old gods rule, old customs linger’ – and suggests that this justified his raping a miller’s wife, who became the mother of his bastard, Ramsay Snow.[217] Bolton said that another northern family, the Umbers, also keep the first night rule (though there is a suggestion that they are secretive about this) as do some of the mountain clans and those on Skagos [ibid.]. The potentially savage enforcement of the right is shown in Bolton’s description of his treatment of the mother of Ramsay. Since the marriage of the miller to this woman had been conducted without the permission or knowledge of Roose, the lord had been cheated. He therefore had the miller hanged and chained ‘and claimed my rights beneath the tree where he was swaying.[218]

Abduction of women, perhaps linked to the old ‘wife stealing’ custom maintained by the wildings, was made a crime by Aegon the Dragon, apparently ‘at the urging of Queen Rhaenys.[219] Such crimes could be destabilising, as was the case with Prince Rhaegar’s ‘infamous abduction of Lyanna Stark, which contributed to a war and the overthrow of the Targaryens.[220]

Homosexuality is disapproved in Westeros (thus the former rent boy, Satin, is despised on the Wall, and a chronicler notes with surprise that the Dornish are not concerned by either male or female homosexual acts,[221] but there is no sign that it is contrary to the law, except, perhaps amongst the Ironmen. Thus, Victarion Greyjoy, finding himself in charge of a group of slaves, weighs the ‘perfumed boys’ down with chains and throws them into the sea, regarding them as ‘unnatural creatures’.[222] And predation by men upon boys may bring punishment: Septon Utt was hanged by Beric for killing boys he molested.[223] In the television series, Joffrey considers making ‘Renly’s perversion’ punishable by death.[224]

Prostitution is generally legal, and brings in tax revenue for the Crown. Cersei Lannister justifies allowing prostitution as a safeguard against ‘common men’s tendency to ‘turn to rape’ if prostitutes are not available to them.[225] Others had not taken the same view. The pious Targaryen king Baelor I the Blessed had tried to outlaw prostitution within King’s Landing, expelling the prostitutes and their children.[226] Stannis Baratheon similarly wanted to outlaw brothels.[227] Neither was successful. The guilt for spreading sexually transmitted diseases might be attached to prostitutes, leading to their punishment, as when Lord Randyll Tarly, orders that ‘a haggard grey faced whore’, accused of giving the pox to four … soldiers’ be punished.[228]

Finally, the television show makes reference to necrophilia, though this is said to be contrary to the King’s law.[229]

Piracy and smuggling

These are crimes in most of Westeros, [II:11] but piracy in particular was regarded as admirable by one group – the Ironborn. There were attempts by Harmund the Handsome, a convert to the Faith, to make sea-reaving a capital offence, but this did not catch on.[230]

Offences of dishonesty

Theft is an offence, and its definition is wide enough to include such conduct as cheating at dice.[231]

There is evidence of regulations concerning adulteration of food, or cheating customers – as in many medieval European cities. Thus Tywin Lannister, acting as Hand for Aerys II (Mad) ‘sternly punished bakers found guilty of adding sawdust to their bread and butchers selling horsemeat as beef.’,[232] and Lord Randyll Tarly sentences a baker, found guilty of mixing sawdust in his flour, to a fine of fifty stags or whipping.[233]

Punishment for crime

Mutilation and capital punishment are the expected consequences of a conviction for serious crimes.

Those found guilty of murder or treason might be hanged or beheaded, often with a sword on a block of wood,[234] or, in the reign of ‘Mad King’ Aerys II, or under Stannis Baratheon, burned.[235] The Eyrie has its own rule or custom with regard to execution – convicted felons are ‘sent out through The Moon Door’ – falling to their death from this lofty exit.[236] An alternative – though whether this is to be considered a post-conviction punishment, or an extra-judicial method of disposal is unclear – is confinement in the ‘sky cells’, cells open on one side over a sheer and fatal drop. This was the fate of Marillion the singer, who confessed to having killed Lysa Arryn, (though he had not) when mad with love. It was thought that ‘the blue would call to him’ (i.e. he would have an insane longing to die) and he would jump.[237] On one occasion, in the Iron Throne jurisdiction, a man who has killed his wife by beating is sentenced to be beaten a hundred times, by the dead woman’s brothers – which, presumably, resulted in his death.[238]

Execution seems always to be done publicly. One custom which has no obvious medieval parallel is the Starks’ practice of the man who passes the sentence also carrying it out.[239] This, claims Eddard Stark, dates to the times of the First Men, whose blood he claims runs in the veins of the Starks. Stark justifies this by saying ‘If you would take a man’s life, you owe it to him to look into his eyes and hear his final words. And if you cannot bear to do that, then perhaps the man does not deserve to die…. A ruler who hides behind executioners soon forgets what death is’. [240] He insists that his seven year old son, Bran, watches him execute a deserter from the Night’s Watch, to familiarise himself with the practice and gain experience for the day when he has to ‘do justice’ in this way. Clearly, Eddard Stark finds it an unpleasant, unsettling experience, since after he has executed somebody, he goes to ‘seek the quiet of the godswood’.[241] Robb Stark also executes in person, beheading Rickard Karstark with an axe.[242] This episode tells us that the formula for such Stark executions is to ask the prisoner before he is killed if he wishes to speak a final word. The Starks do not keep up ‘aspects of the of culture of the North’ such as hanging the bodies and entrails of executed criminals and traitors from the branches of weirwoods.[243] In the Iron Throne’s jurisdiction, bodies, or body parts, may be exhibited after an execution, to deter others from committing crimes.[244] It is not clear that the Starks perform mutilations in person, though Stannis Baratheon did amputate Davos Seaworth’s fingers himself, at the insistence of Davos.[245]

Joffrey has Eddard Stark beheaded for treason, though he claims that he could have had him torn or flayed.[246] Special dishonour is done to the bodies of traitors, so, for example, after execution, Stark’s head is held aloft by the hair for the crowd to see, by Janos Slynt, and Joffrey has it exhibited, though Tyrion orders the removal of spiked traitors’ heads.[247]

Tyrion is sentenced to death when his champion loses in the trial by battle to determine his guilt or innocence of poisoning Joffrey.[248] Men are burned as traitors by the regime of Stannis Baratheon – thus Alester Florent is burned as a traitor.[249] This is likely to have been influenced by Stannis’s conversion to the religion of R’hilor, Lord of Light, which emphasises sacrifice by burning. Differential punishment for treason, by gender, is noted: the male rebels of Duskendale, in the time of King Aerys, were beheaded, while the lord’s wife was mutilated and burned alive.[250] Some traitors and rebels might be pardoned, once they come to the king’s allegiance.[251]

In addition to corporal penalties, traitors (and rebels, if there is a distinction) are subject to property penalties, their lands and titles being forfeit to the crown.[252] Joffrey passes bills of attainder against various people who rebelled against him as their lawful king, stripping them of their lands and incomes.[253]

Genital mutilation appears to be the accepted punishment for rape. Daenerys assumes this,[254] and after the fall of Meereen, she ‘had decreed that …. rapists [were to lose] their manhood.’[255] Gelding as a punishment for rape is noted in Westeros.[256] Stannis Baratheon gelded the soldiers in his army who raped wilding women after his victory in the North.[257] Removal of fingers was the punishment meted out by Stannis on Davos ‘to pay for all his years of smuggling’.[258] A cheat is sentenced to lose a little finger, though is allowed to choose which hand should be mutilated.[259] Losing a hand might be the consequence of poaching,[260] and was formerly the penalty for ‘striking one of the blood royal’.[261] A sailor who had stabbed an archer through the hand for cheating at dice is sentenced to have a nail driven through his palm (even though it seems to have been accepted that the archer had, in fact, been cheating.[262] Those criticising or ridiculing people in power may be disabled from repeating their offence in future. This can be seen in the treatment of a tavern singer and harpist accused of making a song ridiculing Robert and Cersei: he is put to his election of keeping his tongue or his fingers,[263] and tongue-ripping is suggested by Cersei for anyone who questions Joffrey’s legitimacy.[264] Alleged responsibility for spreading ‘the pox’ could be punished by rough and painful cleaning followed by (indefinite) incarceration, as when Lord Randyll Tarly, sentences a ‘whore’, to have ‘her private parts’ washed out with lye before she is thrown in a dungeon.[265] Punishment mutilations do not seem to be done in public, or at least not immediately after sentence, though it is noted that Joffrey, as king, dispensing ‘what it please[s] him to call justice’ from the Iron Throne has a thief’s hand chopped off in court.[266]

Financial penalties may be deemed appropriate for offences of economic dishonesty – so Lord Randyll Tarly sentences a baker, found guilty of mixing sawdust in his flour, to a fine of fifty stags. Corporal punishment in the form of whipping could be substituted if the baker could not pay, at the rate of one lash per stag unpaid.[267]

An element of religious symbolism can be seen in several punishments. A good example is the sentence by Lord Randyll Tarly, doing justice at Maidenpool, on a man who has stolen from a sept. While the customary sentence for theft is apparently loss of a finger, this man is to lose seven fingers, since he has stolen from the (seven) gods.[268] Similar religious symbolism can be seen in the sentence passed by Rhaenys Targaryen on the man who beat his wife to death.[269] Other ‘meanings’ can be attached by varying punishment. For example, Robb Stark condemns a man who complains that he was ‘only a watcher’ of treason to be hanged last – so that he can watch the others die.[270]

Enlisting in the Night Watch might be an alternative to corporal or capital punishment. Those who take the black to escape punishment include poachers, ‘rapers’, ‘debtors, killers and thieves’.[271] Even traitors may hope to be allowed to ‘take the black’.[272] Deserting the Night’s Watch is itself an offence, and appears to be one of very strict liability. Eddard Stark condemns such a deserter as an oathbreaker, and executes him, even though he seems not to be wholly sane.[273]

There is room for discretion in sentencing convicts. An interesting exchange occurs between two Lannisters and the Master of Whisperers over the appropriate penalty for goldcloaks who deserted during the battle of the Blackwater. Cersei Lannister wants them put to death (as oathbreakers). Varys suggests the Wall. Tywin, whose view prevails, orders their knees to be broken with hammers. His argument is that, if this is done, they ‘will not run again. Nor will any man who sees them begging in the streets’.[274] His aim, therefore, is deterrence as well as retribution.

There is a suggestion that punishments are less severe in other jurisdictions. Thus Ollo Lophand, a man of the Night’s Watch, wants to return to Tyrosh ‘where he claimed men didn’t lose their hands for a bit of honest thievery, nor get sent off to freeze their life away for being found in bed with some knight’s wife’.[275]

‘The Faith’ in its criminal jurisdiction is not allowed to impose death sentences, and uses humiliatory punishments, as when Cersei has to perform a naked ‘walk of shame’ through her people for her fornication, her hair being cut and shaved, as was the custom with medieval prostitutes.[276]

Note that the wild Mountain Clans such as the Stone Crows and Moon Brothers, encountered and used by Tyrion, operate some sort of feud/blood price system in the event of homicide.[277]

Part II C: ‘Private Law’

Property Law

Individual ownership of personal property and land (though with feudal overtones) is the norm in Westeros, and acquisition by sale, gift and inheritance is in evidence. Real property may be lost by abandonment.[278] Little more is revealed.

One possibly problematic area is property in dragons. Daenerys Targaryen appears to see them as (her) property,[279] but whether they can be regarded as truly under her control, or should be so regarded, is not entirely clear.

Transfer of property in enslaved people is shown in Daenerys Targaryen’s acquisition of the Unsullied. This is formalised by the passing to her of a whip. She throws away the whip to symbolise her freeing of the Unsullied.[280](For more on property in people, see above, section on slavery).

The television series provided a fine passage in which Tyrion Lannister attempted to explain to his jailer in the Eyrie something of ideas of personal property (though one might quibble with his use of ‘possession’ here): ‘Sometimes possession is an abstract concept. When they captured me, they took my purse but the gold is still mine’.[281] I am sure that there is much one could say about the property/contract borderline in relation to the frequent trotting out of the tag that ‘A Lannister always pays his debts’. At times this is used in a wider sense as well.**

Some marginal and ‘foreign’ cultures take a different view of the appropriate relationship between people and things or land, and the appropriate modes of acquisition of property.

A notably different view persists amongst the Ironborn. Fittingly, the motto of House Greyjoy is ‘We do not sow’,[282] and their ‘Old Way’ praises and asserts religious justification for those who ‘reave and rape’ [ibid.]. An interesting gender distinction is made: in the Old Way, whilst ‘women might decorate themselves with ornaments bought with coin’, there was a more demanding requirement for ‘warriors’, who were allowed to wear only the jewellery they took from ‘the corpses of enemies slain by his own hand’. This was known as ‘paying the iron price’ for the jewels.[283] It was also applied in other contexts, such as the acquisition of a crown, and of land.[284]

The Dothraki do not acquire property through sale, but through a system of (semi-) reciprocal gift-giving,[285] and do not have a strong concept of individual property since they see it as appropriate for members of a former khalasar to remove the ex-khal’s herd: ‘it is the right of the strong to take from the weak’.[286]

Also far from Westerosi concepts is the view of the Wildings. Ygritte expresses views reminiscent of some native American or aboriginal peoples, disputing the idea of individual ownership of (some?) land and chattels, which are worth quoting in full: ‘The gods made the earth for all men t’ share. Only when the kings came with their crowns and steel swords, they claimed it was all theirs. My trees, they said, you can’t eat them apples. My stream, you can’t fish here. My wood, you’re not t’ hunt. My earth, my water, my castle, my daughter, keep your hands away or I’ll chop them off, but maybe if you kneel t’ me I’ll let you have a sniff. You could call us thieves, but at least a thief has t’ be brave and clever and quick. A Kneeler only has t’ kneel.’[287] On personal property, it is a bit all over the place, if we take into account the episode in the television series of Ygritte taking away Jon Snow’s sword (it’s made of Valyrian steel, you know …) possibly in some sort of recompense for the ‘debts’ she says he has because she saved him. When he objects, she comes up with the head-scratcher ‘I stole it. It’s mine. If you want it, come steal it back.’[288] So is there property or not, Ygritte? Or is ‘stealing’ not a removal of property?

The ‘feudal’ element

Lordship and feudal ties are much in evidence, though little explained. High lords have bannermen, bound to them by oaths, though the connection with land grants has not been explored, and no doubt there is more to say about the rights and responsibilities of lords and ‘smallfolk’. It is clear that (some?) people can choose to whom they swear themselves – e.g. Brienne of Tarth swears to Catelyn Stark in what seems more like a personal bond than something land-related.[289]

Wardship is a known institution, though it is not always well-distinguished from fosterage and hostageship. Thus Theon Greyjoy is said to be the ward of Ned Stark,[290] but is in reality a hostage for his father’s good behaviour following a rebellion against Robert I Baratheon]. Shades of King John of England, in particular.

Money It is interesting to note that there is no equivalent to the medieval Christian horror of usury. The Iron Throne pays ‘usury’ on its loans,[291] and Cersei tells merchants to pay usury on their own loans from the Iron Bank of Braavos.[292]

Succession

Medieval common law (and other medieval legal systems) had somewhat different rules for succession to the throne from those prevailing in relation to land (and different rules again for succession to personal property). There is, likewise, some suggestion of a distinction in the laws of Westeros at the time of the Song cycle between rules for inheritance of land and rules for succession to royal and noble titles, but the matter is not always clearly differentiated. In both sorts of succession, the model which seems to be predominant is male primogeniture, for legitimate children only. The eldest son is regarded as heir to family land, titles and also to such personal property as Valyrian steel swords.[293] There are, however, ways to alter the succession, some local differences, and some disputed issues.

There are signs that there was, in the time before the Song cycle, a less absolute tendency to male primogeniture in Westeros. It is noted, for example that there had been some question of female succession in the Riverlands, though this was rejected,[294] and that Alysanne, sister and wife of Jaehaerys I Targaryen argued with her brother/husband over succession, taking the position that males did not always have to be preferred to females – so that the granddaughter of an eldest son should succeed to Dragonstone in preference to the second son’s heir apparent.[295]

At a Great Council held in the year 101 AC (After the Conquest), however, there was a decision that, with regard to succession to the Iron Throne, women were to be excluded. Not only were men to be preferred to women, but women simply were not to be allowed to take the throne, and, furthermore, nor could a woman transmit a claim to the Iron Throne to her descendants.[296] This, of course, looks somewhat like the ‘Salic Law’ insisted upon by the French from the fourteenth century, to exclude the descendants of Isabella, wife of Edward II of England. Not everyone accepted this as an ‘iron precedent’, however, and King Viserys I Targaryen declared his daughter his heir, and continued to take this view even when he had a male child with a subsequent wife. Clearly seeing that this might be opposed, this king, like Henry I of England, had tried to ensure that his settlement would be respected by demanding the promises of his nobles, many of whom did homage to the nominated heiress.[297] As in Henry I’s case, however, such promises did not prevent a civil war over the issue.[298] The strong ‘no women’ rule seems to have gone by the time of the Song cycle, since it is assumed that Myrcella has a chance of succeeding, and even the pedantic Stannis Baratheon assumes that his daughter Shireen will inherit the Iron Throne which he takes to be his, if he and his wife do not produce male heirs.[299]

By the time of the Song cycle, it is clear that descendants trump collaterals – so a maester in White Harbor tells Davos that a son must come before a brother (in terms of royal succession: ‘the laws of succession are clear in such a case.’[300], so that Tommen beats Stannis as heir to the Iron Throne after Robert I Baratheon, assumed father of Tommen, and definitely brother of Stannis, though not, of course if Tommen was shown to be a bastard. The law also provides that the child of the first son took priority over the second son,[301] and that girls are not barred from succession – just postponed to males of the same rank. Thus Alys Karstark notes that a daughter comes before an uncle (John and Eleanor of Brittany, anyone?).[302] As with many actual medieval realms, the existence of agreed inheritance customs or laws does not necessarily stop those with tenuous claims having a go – thus Renly, Robert’s younger brother also tries for the crown. Renly accepts that Stannis has the better claim in law, but calls it ‘a fool’s law’, asking ‘Why the oldest son and not the best fitted?’.[303] He rejects Catelyn Stark’s suggestion for a Great Council to decide who should reign, considering that the outcome should rest on strength, not talk.[304] He argues that Robert did not really have a right either, though various arguments based on past marriages to the Targaryens were made. He argues from strength of numbers.[305]