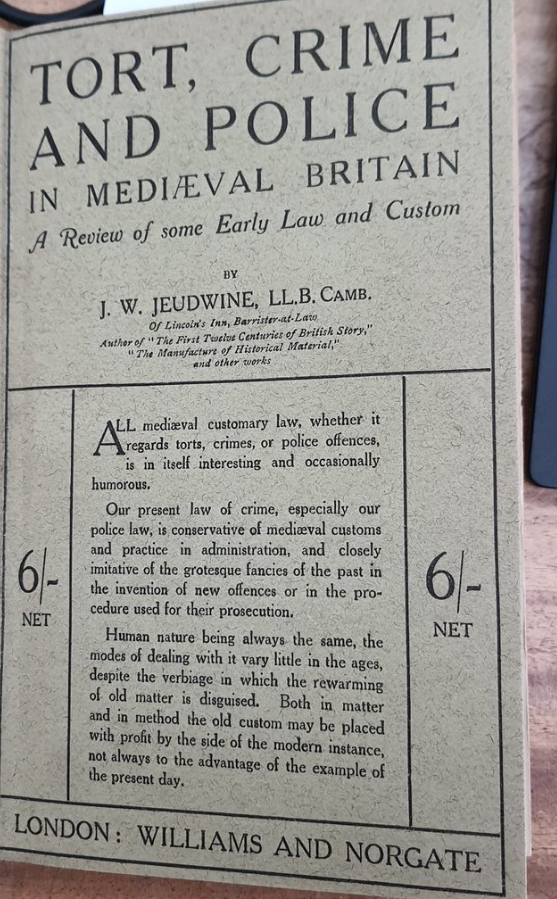

Today’s searching in old law books for references relevant to my mayhem project took me to a book, and an author, I’ve not encountered before (though he has made it onto HeinOnline, and was, apparently, the author of some other, cracking-sounding reads on agricultural holdings, land and contemporary criminal procedure): John Wynne Jeudwine (1852-1928).[i] He was a barrister, a fellow of the Royal Hist. Soc., and clearly had a sideline in law and history books. The one I was looking at was his Tort, Crime and Police in Mediaeval Britain (1917) (a snip at 6/- !). I picked it up on an open shelf, but it is in fact also there on archive.org. It did have a little bit which will come in handy in relation to mayhem and the tort/crime borderline, but also some excruciating views about one of the big issues of the day – the possibility of women becoming barristers like him (p. 239 ff, stop before you get to police and clairvoyance …)

I suspect that our John thought himself quite a wit and stylist, and he came up with the following killer (and in no sense self-satisfied) argument about the issue:

- Being a barrister (like him) is, like, super hard (Elle Woods would, later, get this so wrong)

- Most men can’t do it, coz, like, you have to have a really good personality (like him)

- Even fewer women would be able to do it, obvs, (‘not one in ten thousand’) because, like, to do that, they would have to have a weird, unwomanly, sort of personality (battleaxe, shrew, hag, etc., only really quiet?) ‘the rather hard, rather mediaeval [what??] temperament essential for the advocate [like him!]: a combination of courage, judgment and silence’. Those ladies! They can’t keep quiet, now can they?

- So why not let them try? Might be a laugh, eh?

- In any case, they could be useful for the rubbish bits of barristering, and go to the police court. There they could do things which ‘intimately concern’ women – bad mothering and having verminous children, and, it is implied rather than set out explicitly, being a ‘common prostitute’, soliciting etc. This would be good for them, and for the law, because, apparently, men didn’t know about women’s stuff and women don’t know about ‘the conditions attending a life of poverty’ (well, apart from the ones with vermnous children or being accused of soliciting, I suppose …). Excellent!

- And obvs they shouldn’t have to wear a wig. [This is really important, and I am sure Helena Normanton and her sisters would have been glad to take up the suggestion that ‘[surely] their artistic sense [women are naturally artistic, innit?] could be trusted to design some academic headgear suitable to the woman lawyer…’ [I mean, wigs are stupid, but possibly better than a woman’s hat of that period would have been… think of the classic early women barrister pictures like this one without those wigs!).

- Or charge the male going rate (the dears were not to be ‘tied down’ to charging the same as men – clearly that would be ridiculous!).

Sorted! Thanks Mr Jeudwine!

Wonder how he reacted to the entry into the profession of women. I suspect some of the trailblazers would have made mincemeat of him [when not suppressing a desire to talk loudly about the best design of hat, and how great it is not to have to get paid the same as other barristers!]

[i] Times, Tues 1st Jan, 1929, p. 1.