Another little bit of Year Book/Plea Roll matching – this came up tangentially in a bit of petty treason research today, and seemed worth a quick word and thought.

When I say matching … it is not quite an ‘X = Y’ situation: more of an X probably = Y, Z or A.

The Year Book case is YB Trin. 6 H VII f 5 pl 4 (Seipp 1491.020). The plea roll entry is one of three possibles on the King’s Bench roll for Trinity 1491.

The candidates are:

- KB 27/920 Rex m. 5 (AALT IMG 209) This is a case from Berkshire before John Horne, in which Richard Patte of Sulhamstead, clerk, was alleged to have raped a widow, Margaret Huys, lately wife of John Phelippe.

- KB 27/920 Rex m. 3d (AALT IMG 463) This also comes from Berkshire, from John Horne’s tourn. John Hyde, recently of Sonning, clerk, was alleged to have raped Elizabeth, wife of James Trell.

- Yes, it’s Berkshire and John Horne again! KB 27/920 m. 3d (AALT IMG 465): Stephen Bregyn, clerk, was accused of raping Alice Robyns, wife of John Robyns.

Or perhaps it is an amalgamation of all of them – since they are all saying the same thing.

The YB case is not about petty treason at all – though there is a passing reference to that in the reported argument – it is a case about jurisdiction over rape. Who could hear rape cases? Could low-level criminal courts hear them? Let me be up-front about one thing: there is a difference between YB and PR in terms of which courts are mentioned – the YB is interested in courts leet, whereas the PR entries are all about sheriffs’ tourns. Since there is nothing on the roll specifying courts leet, I think I have to assume that one of these is the best match. Possibly these tourn cases prompted a wider discussion of low-level jurisdiction.

The successful argument against lower courts having jurisdiction in this area, as it appears in the YB, is that they only have jurisdiction over felonies if they existed at common law rather than having been created by statute, and rape as a felony was a creature of statute. A choice had been made to limit such jurisdictions, and/or that it was seen to be fitting to keep them to the things they had been able to do ‘since time immemorial’, or at the time of the (certain or assumed) grant of jurisdiction.

The issue about sheriffs and rape jurisdiction was not new – I wrote a blog post about this issue as it arose in 1482, in the not-too-distant past (it’s here). A bit odd, then, that tourns are still being used in this way, and it’s still thought worth reinforcing via YB reports that this is not OK. Suggests something of a lack of influence of common lawyers on practice in the low-level criminal jurisdictions, I think (though, as ever, I am ready to be told that I am missing something important …). I do wonder what was going on with John Horne’s tourns in Berkshire.

As far as the rape cases themselves go, well, nothing very surprising. the accused all ‘walked’ after having paid a fine to the king (to save the bother of a trial for the trespass element of the charges).Each of these fines was 5s – a pretty common amount, according to the list of fines in the plea roll – and, according to the National Archives currency converter that represented about 8 days of wages for a skilled tradesman. Moderately costly then, I suppose. Whether or not there was any other settlement, compensating the women themselves, will remain a mystery.

GS

13/9/2021

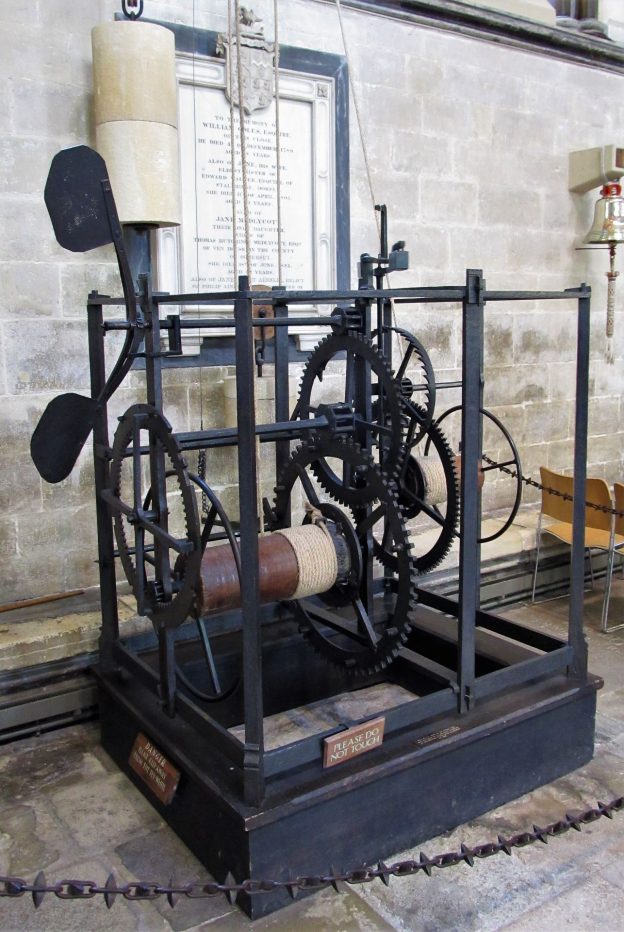

Image – to fit in with my contrived title, it’s a medieval clock! From Salisbury Cathedral. Yes I do know that isn’t in Berkshire, but best I could do. From Wikimedia Commons.