[see also my post on this for the Bristol Law School bkig]

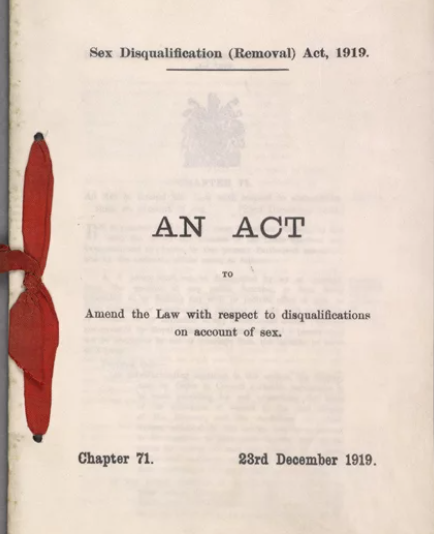

Centenary commemorations of an important step towards inclusion of women in the legal system of England and Wales will soon be upon us: it is almost 100 years since the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919 removed sex as a disqualifying factor for participation as a juror. Obviously, and importantly, this did not lead to equality either between men and women, or between women in different categories in terms of wealth, class, education or ethnicity. Nevertheless, it was a significant victory, won by persistent and righteous effort, and it deserves to be marked.

While the Act meant that women could be jurors, it also gave judges a discretion to choose a single sex jury (s.1)[i] This power could be used to exclude women from cases thought inappropriate for them. Excluding women was its usual function, but the section does envisage women-only juries too, ‘as the case may require’. Cases, it seems, were not thought to require women-only juries, for almost half a century following the act, but there is an interesting case from the late 1960s in which a judge decided to use it in an unexpected way, excluding all males from a jury. It is with this case that this post is concerned.[ii]

The case concerned the death of a small child: Miya Bibby Ullah – a girl of three – in South Wales, in February 1968. The girl had died after having been scalded in a bath by her aunt, the accused, Margaret Ann Sutton, of an address in Cardiff.

The decision to order a women-only jury was made by Thesiger J when he heard the case at the assizes, in Swansea. Both the reasons for his decision and the responses to it are interesting. There are slightly differing accounts of Thesiger J’s reasoning, but there seem to have been two things which pushed him to insist on a female jury: (i) this was a case about child care, and women would know more about that than men, and; (ii) there was a need to have some insight into the feelings of women. “The judge said he felt that this was essential because it involved the bathing of a baby and the feelings of women were concerned.”[iii]

Leaving aside the gender stereotyping involved in this, it might seem that, if this was a matter of ‘expertise’, then witnesses, rather than jurors, would be able to provide it. It shows a strange lack of faith in male jurors to imagine them incapable of weighing up evidence relating to child care or feelings. The actual reasoning might have been a little different: it was not that men could not understand these matters – indeed, it was not that there was actually a need for an entirely female jury, but Thesiger wished to ensure there was a significant female presence in the jury, and the Act did not allow him to stipulate quotas of males and females, only all one or the other.

It is clear that the decision was Thesiger J’s own – in fact both the prosecution and the defence objected to his order, and the defence used it in an appeal. These objections are worth some consideration, as the lawyers do rather tie themselves in knots.

According to the Times report,[iv] Sutton’s counsel, Aubrey Myerson QC, said that making the order for an all-women jury would be an abuse of the judge’s discretion. What was his objection? The case was too emotive for a jury of women to be able to hear and decide without the steadying influence of a man or men: “this was a case which was emotionally power-packed, and to empanel a jury solely of women would present great problems because of that. It was going to be very difficult for 12 women without stability of any man being present, to apply an objective mind without partiality to the evidence in the case”. This says interesting things about women’s perceived inability to function rationally when faced with upsetting circumstances, if not helped by a man. There are, of course, implications in terms of what was supposed to happen when juries included both men and women. Myerson also made a comment straightforwardly denigrating women’s intelligence: [any jury of women was] not going to apply to the facts of this case the breadth of vision normally given by a jury in which there were men.” There we are – men: breadth of vision and their presence serving to broaden the vision of poor, narrow-visioned women. It might of course be that women in a mixed jury should just shut up and let men give full expression to their breadth of vision.

Myerson had a better point in relation to the judge’s assumption that just by being female, women jurors would be able to understand the accused: they were not, he said, going to be “a jury of women in the same age group as Sutton, or with the same background or intellectual capacity of the accused”.

The prosecution (T. E. Rhys Roberts) also objected to the order, on the ground that the subject matter was too upsetting for women: “the emotive value of injury or death to a child on a woman … would take it outside the bounds one expected of a jury”.

There was an attempt by the defence to change the jury by way of multiple challenges, but they were simply replaced by other women. The case proceeded.

Myerson, having lost on the question of an all-women jury, attempted to use the sex of the jurors to his (client’s) advantage, exhorting them: “In your historical role, the part you have to play is to show, in the discharge of the duties you have undertaken, that you can demonstrate to one of your own sex that high degree of fairness, that high degree of impartiality, and a complete lack of bias that reflects on your part an understanding of the mind of this woman in circumstances that can only be reflected by the acquittal of this woman.” An interesting, cajoling, tactic, but one which did not work for him: Sutton was convicted and sentenced to five years in prison.

Although the law reports do not mention this, newspaper sources all describe the child as ‘coloured’. Clearly, this seemed to them a relevant fact. Nobody else is described in racial terms. It looks as if the inclusion of the child’s ‘colour’ is less about diminishing the loss or offence, and more about building up a picture of what many readers would consider the undesirable and disorderly family life of the Suttons. Thus, the accused was a ‘spinster’ mother of two, with another on the way, from Splott (a poor part of the city) and there were hints that she had been moved to treat the child unkindly because her television watching had been interrupted. The fact that she was ‘unemployed’ was noted. The ‘mixed race’ of her sister’s child might well also have suggested to some that the Sutton sisters were ‘no better than they ought to be’.

There is also some comment on the female jurors: newspaper reports tell us that one of them could not read the oath; that they were “middle aged”, and that half of them had changed outfit from one hearing date to the next. Whether that last point is emphasising the frivolity of the outfit-changers or the poverty of the re-wearers is not clear (but the attire of male jurors is not much commented upon).

Sutton appealed against conviction and sentence, in part based on an argument that there should not have been an all-women jury. Her counsel at the appeal argued that having an all-women jury had been unfair to her, because the details of the case were “so harrowing that prejudice was likely with an all-women jury”.[v] No prejudice in that remark at all.

The Court of Appeal (Lord Parker LCJ; Ashworth J; Davies LJ)[vi] expressed disapproval of the use of the all-women jury ‘even if the case was highly emotional’. (There is some disagreement in the establishment as to whether women’s ‘emotional’ ‘nature’ is a good or a bad thing in terms of fitting them for jury service. I may not have the breadth of vision to understand it, of course). The court did not agree that Thesiger J had acted beyond his powers or in an arbitrary way, however. The conviction and sentence stood and the possibility of all-women juries remained in theory, though Sutton did not lead to a flood of similar orders for all-women juries.

Two things would be interesting to know: (i) why did this suddenly crop up so long after the Act; and (ii) what sort of cases were originally envisaged as likely women-only jury cases? In addition, it would be interesting to see the papers relating to this case which are in the National Archives, but not due to be opened until 2044. One for legal historians of the future.

Sources:

R v Sutton (Margaret Anne) (1969) 53 Cr. App. R. 128

Times Tuesday, April 30, 1968, 4; Wednesday, May 01, 1968, 4; Thursday, May 02, 1968. 5; Friday, May 03, 1968, 3; Tuesday, Nov 19, 1968, 7;

http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C4630609

Guardian 19 Nov 1968, 5.

Daily Mail 3 May 1968, 4.

Anne Logan (2013) ‘Building a New and Better Order’? Women and Jury Service in England and Wales, c.1920–70, Women’s History Review, 22:5, 701-716.

[i] Anne Logan (2013) ‘Building a New and Better Order’? Women and Jury Service in England and Wales, c.1920–70, Women’s History Review, 22:5, 701-716

[ii] Logan, 705, 706.

[iii] Times (London, England), Apr 30, 1968, 4.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Guardian 19 Nov 1968, p. 5.

[vi] R v Sutton (Margaret Anne) (1969) 53 Cr. App. R. 128