Aside from its association with some Scots poet or other, 25th January is, as we all know Dydd Santes Dwynwen – the day of St Dwynwen, ‘patron saint of Welsh lovers’ or ‘Welsh patron saint of lovers’, depending how exclusive or expansive one is feeling.[i] It is a funny old business, this celebration of Dwynwen: a mix of medieval poetry – [see Dafydd ap Gwilym’s invocation of Dwynwen here in Welsh and here in translation] -, historical snippets, (not-so-old, somewhat inconsistent, and sometimes nasty) stories and the modern cultural politics of Cymreictod, (proud) Welshness. If Dwynwen is new to you, the place to start is Dylan Foster Evans’s piece here. To summarise, the now-standard story features a 5th C Welsh princess, a suitor pressing for sex, a divine intervention involving ice cubing, a prayer and a retreat to a convent. The Dwynwen-related story which I came across recently, and have decided to inflict upon all those stumbling over this page, is a bit different: neither as magical (no ice cubes, no wishes) nor as attempted-rapey as the St Dwynwen story itself, but I think it has some pondering points nonetheless.

The year is 1904 and the scene is the National Eisteddfod, this time taking place in (Y) Rhyl, a seaside town in North Wales. As was customary, the in-crowd at these affairs, the Gorsedd of Bards, headed by the Archdruid, Hwfa Môn, were admitting various notables to their order. The first so admitted as an honorary ‘Ovate’ (ofyddes) was one of Queen Victoria’s many grandchildren, Princess (Marie) Louise of Schleswig Holstein.[ii]

Princess Louise did not obviously have any connection with Welsh culture. As a letter reveals, she had not known about the Gorsedd before the visit in question, and, in her response to an address by the town clerk of Rhyl, at the Eisteddfod, she had noted that this was her first time at such an event. There was no requirement of proficiency in Cymraeg at that time, for acceptance by the Gorseddd, nor, indeed, was such a requirement imposed until pretty recently, and, though she had some other languages, including, of course, German, she was not a speaker of Yr Hen Iaith. Her 1956 memoir, My Memories of Six Reigns,[iii] says nothing about the Eisteddfod, or Welsh culture. I have seen no evidence of a lasting interest, either. Nevertheless, she was apparently cheered, and made a good impression. She sent Hwfa Môn a signed photo of herself, and some pictures of the Gorsedd which she had snapped, receiving in response a short formal poem in Cymraeg, an englyn, ‘Englyn I “Dwynwen”’,[iv] which perhaps somebody translated for her. And when HM lay dying the following year, the Hon Mrs Mary Hughes of Kinmel, a royal lady in waiting, who had also been Gorsedded in 1904, was a keen enquirer after his health. That is all my quick research foray could unearth, as far as her post-Eisteddfod connection with the Gorsedd was concerned.

All slightly irksome from a political and cultural point of view, perhaps, this toadying to a woman because of her royal lineage, but what has the incident to do with Santes Dwynwen? Well, along with having a ribbon bound around one’s arm (a ribbon which may have been green or blue or red, depending which account is consulted!) one of the perks of being received into the Gorsedd circle was and is the bestowing of a by-name (ffugenw), and the princess (hardly short of names, already having been given this little list: Franziska Josepha Louise Augusta Marie Christiana Helena!) was given the name … Dwynwen. Little explanation was given for this choice, in the newspapers which picked up the story.[v] It did strike me as rather intriguing, though.

To the extent that newspapers commented on the name at all, they emphasised non-christian interpretations. For the Chester Courant, the name Dwynwen signified ‘the British goddess of love’, and elsewhere, she was ‘a goddess known to the mythology of Ynys Môn [Anglesey]’ or ‘the Celtic Venus’. Some of those present at the Eisteddfod would have known the tale of Santes Dwynwen, and her designation as nawdssantes cariadon – patron saint of lovers.[vi] ‘St Dwynwen’ was in hearts and minds in Wales, as can be seen from the fact that an imposing cross with an inscription to ‘St Dwynwen’ had been erected on Dwynwen’s ‘island’, Llandwyn, as recently as 1897. Hwfa Môn, as both a ‘descendant’ of Iolo Morganwg and a native of Ynys Môn, cannot have been unaware of her story. So, why the choice of ffugenw for the princess?

Was the association between Dwynwen and Louise a nod to her sad marital history? Married to a German royal, one Prince Aribert of Ansbach, in 1891, her marriage did not go well. In her memoir, Louise refers to her love life in quite moving terms, calling her marriage ‘a sad and tragic chapter’ and something which she ‘thought was going to be so perfect’, but which ‘ended, alas, in disaster’ (p. 110). There are no juicy revelations, or nothing which would get modern readers excited, but it was probably quite something, in 1956, to have a princess saying that:

‘As time went on, I became increasingly aware that my husband and I were drifting father and farther apart. I had no share in his life; there was not that real companionship and understanding between us, which, after all, is the true foundation of a happy marriage. In fact, I was not wanted, my presence was irksome to him, and we were two complete strangers living under the same roof. We occasionally met at meals and when we had guests, otherwise days might pass without our ever seeing each other.’

And that she had moved from being an ‘enthusiastic girl’ to a ‘disillusioned woman’.

(Louise c. 1890, portrait by Josefine Swoboda)

Aribert and Louise’s nine-year marriage was annulled by her father in law, who apparently had the right to do this arbitrarily. I have to say that I am not on top of the detail of Ansbach family law (fascinating though I am sure it is) but the use of the terminology of annulment suggests that, as far as that law was concerned, it was as if the marriage had never taken place. Louise, however, took seriously the fact that she had been married before God, according to the rites of the Church of England, and did not, apparently, seek another husband, but accepted a single life. Aribert lived on until the 1930s. Was the choice of ‘Dwynwen’ an allusion to her lack of luck in love, or her need of the aid of the nawddsantes cariadon?

Whether or not it had that ‘spin’ to it, there is a bit of a parallel between Princess Louise and the Santes Dwynwen of the standard story. That Dwynwen, after the whole block of ice and praying business, went off happily to spend her life as a nun. There was no possibility for Louise of entry into a convent, but we might see as slightly nunnish the way that she did go on to spend a large proportion of her time on all sorts of charitable endeavours and good works, as well as taking an interest in arts and crafts. Dwynwen was a patron saint, Louise a patron of various well-meaning organisations. A princess of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, however, was bound to be treated as rather more trivial than her fifth-century namesake. Reporting on her attendance at a craft/industrial event just before the 1904 Eisteddfod, journalists were unable to stop themselves focusing on the fact that she was ‘gracefully attired in a pale pink dress with a pink chip hat trimmed with roses’. We hear a lot less about Santes Dwynwen’s outfits.

GS

20/1/2023

[i] For some reason, she is also associated with patronage of sick animals – not sure what sort of a spin that puts on Welsh ideas about love. Let’s not go there.

[ii] For some biographical details, see the ODNB entry, if you have access: K. Rose, ‘Marie Louise, Princess (1872-1956).

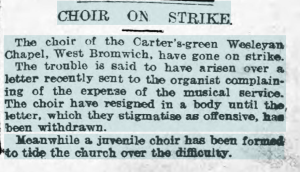

Much Druidic and Pan Celtic costumed business followed and surrounded all of this. The papers also report the competitions, including, interestingly, a prize for ‘the best chart or map showing the changes effected around the Welsh coast by the encroachments and recessions of the sea since the year 1800 – winner, Mr E M Lewis, Rhydyclaidy, Pwllheli. There was some grumbling about aspects of the Eisteddfod, and about the institution itself, as ever.

[iii] (slightly less controversial than Spare …) Marie Louise. 1956. My Memories of Six Reigns. London: Evans Bros. My memories of six reigns : Marie Louise, Princess, granddaughter of Victoria, Queen of Great Britain, 1872-1956 : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive

[iv] (nicely crafted but not that exciting, to my inexpert mind – images of sunshine etc.).

[v] The event was picked up by newspapers in Wales, See, e.g., this and this. And, in Cymraeg, this. and also made an appearance in the UK national press: see Times Weds Sep 7 1904 p. 8. Manc Guardian Weds Sep 7 1904 p. 6.

[vi] For nawddsantes cariadon, see, e.g. this 1895 report.

Postscript

Continuing the comments on St Dwynwen and the phenomenon her day (see main post), there was the occasional comment on this in the UK press, from the 1970s. Somebody quickly used up one obvious title, in the 1972 Guardian article, ‘Funny Valentine’[i] (6th December, 1972) to give a rather sneery – and yet still interesting – account of the movement to ‘make St Dwynwen’s Day happen’.

James Lewis reported on the campaign by a Welsh publishing house, Y Lolfa, to drum up interest in the new or revamped feast, marketing cards on the model of the Feb 14th version. They were producing two ‘nice’ cards and one ‘naughty’ card. Obviously we wanted to know about the ‘naughty’ card first. This had a picture of ‘a young lady’s legs’ with the word rhyw x 6. This was a less-than-subtle play on words, because rhyw means ‘some’, but also ‘sex’ (and actually a number of other things, but let’s not over-complicate). So there you go – rude! Do wonder how many of those they sold, and how they were received. The ‘nice’ cards featured one (rather sickly, to my mind, but perhaps that’s just me being jaded) pun Pwy sy’ wedi dwyn fy nghalon i? (Who has stolen my heart? – playing with the Dwyn in Dwynwen and the verb ‘to steal’), and a rather old-fashioned sounding Cofion cariadus ar Wyl Dwynwen (Loving greetings on the feast of Dwynwen. Although some doubted the likelihood that the cards would be popular, Lewis noted that Y Lolfa had been successful in their sales of a Christmas card of Prince Charles with ‘a greeting in pidgin Welsh’. Mocking the pretentions of the man who is now (Not My) King Charles III, or affectionate, I wonder.

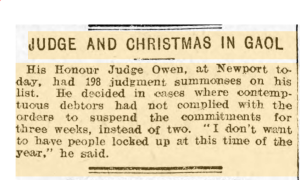

[i] Now there’s a song … apart from the fabulous Ella Fitzgerald recording of it, there are some splendid rhymes – e.g. ‘laughable/unphotographable’.