Not too long ago, I noted a case from 1418/19 in which a woman called Marjory appealed two men of offences relating to the death of her husband, John Chaloner, only to be appealed herself for this same death, and being convicted, and, apparently, burned, for ‘petty treason’ (see this blog post). Well, now another of these double appeals has turned up: cue a bit of comparing and contrasting!

A pair of entries on an Oxfordshire gaol delivery roll for 1407 tell us that Emma, widow of John Handes, had come and appealed Roger Sutton of the death of John her husband, giving the required pledges for prosecution. Her appeal alleged that, on Wednesday 6th July 1407, at Chipping Norton, Roger had killed John with a dagger (price 1d), feloniously. Rather than pleading guilty and going to jury trial, as I was expecting, Roger decided not to put up a fight – he said he could not deny this, and so all that was left for a jury to do was to appraise his assets. There was not much to appraise: there were, apparently, some clothes, worth 20d, but no land or other goods or chattels beyond the clothes. The man himself was to be hanged.

The second appeal was by William Handes, brother and heir of the deceased John. He appealed Emma of the death of John, and his pledges to prosecute were noted. His appeal explained that Roger had done the actual killing, but Emma advised and ‘consented’ to it. She was also alleged to have paid Roger for his felonious work (2s). Unlike Roger, Emma was ready to fight. The jury found her guilty though, and sentenced her to burn. Emma had no assets, it was recorded. She did not burn, however: first she had the sentence deferred, by claiming pregnancy, and having this confirmed by a ‘jury of matrons’. Generally, deferral means deferral, but, in this case, this period seems to have given Emma a chance to seek a more permanent way to avoid execution: according to the patent roll, she was pardoned.[i]

Spot the differences?

Clearly, the later Chaloner case and this one share a basic pattern: W appeals X for the death of H; H’s brother and heir appeals W. X and W are both sentenced to death; W claims pregnancy. There are obvious differences, in that the pregnancy claim is accepted in Emma Handes’s case, but not in Margery Chaloner’s, and in that Emma manages to secure a pardon (whereas, as far as my investigations have been able to establish) there was no such pardon for Margery.

Another difference is that there is not the intriguing overlap in personnel in the Handes case which we see in the Chaloner case: in the latter, both of the widow’s pledges to prosecute were apparently relatives of the deceased husband, including the brother who would appeal her; in the Handes case, that is not obviously the case. Following on from this, while I do wonder whether there might have been some pressure or deception in the Chaloner case, helping Margery to bring an appeal against others, and then appealing her too, to ensure that everyone involved was convicted, or, indeed, to get rid of somebody who would have had claims on the deceased’s property) it is harder to see that in Emma’s case. It is still hard, however, not to be suspicious that the motives of her brother in law in appealing her might not have been entirely about getting justice for his brother.

It is worth a brief word about the pregnancy deferral-pardon element of the Handes case as well. Here we see the jury of matrons in action. The fact that they found her to be pregnant suggests that she was in a fairly advanced state of pregnancy, but the months allowed to her presumably gave her a chance to make her request for a pardon. Just what lay behind that is unclear – was the allegation of her involvement found to be trumped-up nonsense, or was there some other reason for the exercise of mercy? The short note of the pardon does not tell us, unfortunately.

A final intriguing element is that, as well as her pardon for the conviction on the appeal brought by her brother in law, Emma Handes also received a pardon for another appeal, in this case brought by a certain Roger Taillour of Chipping Norton. Could this be the same man as Roger Sutton? And where is this approver appeal? I haven’t turned it up yet, though it seems unlikely that it is made up. If it does exist, it brings in yet another dimension to the case – some sort of odd vicious triangle, which certainly needs some more thinking about. There may be another instalment, if I find more …

GS

12/9/2021

[i] CPR 1405-8, pp. 371, 470, 10 Oct 1408.

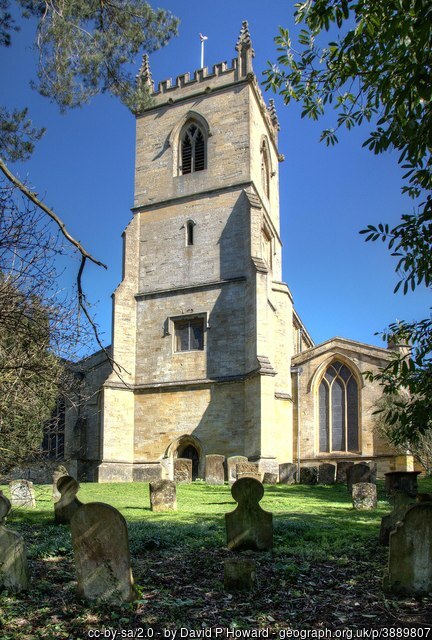

Image – slightly gratuitous church. It’s St Mary’s Chipping Norton. Well somebody probably went there at some point, in between all of the killing and accusing, didn’t they?