Content warning: concerns historical records relating to sexual violence, and historical attitudes to such violence which are, without question, offensive.

An entry on the King’s Bench plea roll for Easter 1435 tells us about proceedings against a Norfolk clerk, Thomas Hervy of Testerton.[1] Amongst other things, he was alleged to have broken into the house of John Serjeant of Colkirk, on 1st October 1433, and to have wounded Margaret, John’s wife, by stabbing her with a lance or dagger. He was, eventually, acquitted. So far, so run-of-the-mill: medieval legal records are full of accusations of non-fatal injuries of one sort or another, comparatively few of them resulting in conviction, and we know that carrying a knife or dagger (if not a lance) was commonplace. The reason for drawing attention to this case, is that it is one in which it really is neither a dagger, nor yet a lance, that we should see before us, and that may have some important implications.

Allegations of misconduct involving the use of weapons are strewn through the records of the medieval English central courts, even when we can be fairly sure that nobody thought they had actually been used. They appear as ‘boilerplate’ text, in litigation relating to what a modern common lawyer would regard as torts, a fearsome list of swords, staves, bows, arrows and sometimes other weapons featuring, routinely, and often incongruously, in allegations of trespass of even a relatively mild sort, as a means of gaining entry to the king’s courts.[2] Given this background, it may appear rather banal to point out that I do not think anybody ever believed Thomas had actually attacked Margaret with a bladed implement, but this short record does take us in a disturbing new direction. The entry is not an embellished version of a lesser offence, done for jurisdictional reasons, but one offence presented as another, for what we must probably see as entertainment, for the real allegation was not one of stabbing, but of a sexual offence.

Let us take a closer look at the record of the Hervy case. It gives more specific names to the weapons alleged to have been used, breaking from Latin into English as it does so. Hervy ‘wounded’ Margaret with a ‘carnal lance, called in English a ballokhaftitdagher’, (a ‘bollock-hafted dagger’ in more modern English). I believe that this would have been understood to be neither a lance nor a dagger but a penis: the offence was not a ‘wounding’ in the conventional sense, but sexual penetration of John’s wife.[3]

This position needs some justification. Lances, of course, were real weapons, though a ‘carnal lance’ seems rather obviously phallic. As for the dagger, while there was a real weapon called a ‘bollock-hafted dagger’ (also known as a ‘ballock dagger’ or ‘ballock knife’) in medieval and early modern Europe, named for its distinctive two-lobed hilt, [4] I do not think that this was understood as a real bladed implement either. The juxtaposition of a ‘lance’ and a dagger (which would seem to be things of rather different dimensions) suggests that there has been a slip into a metaphorical mode, and the equation of the ‘carnal lance’ and ‘bollock-hafted dagger’ is hard to explain other than in their common representation of male genitalia.

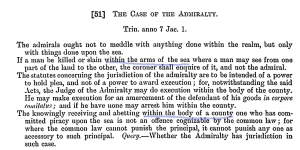

There are a few cases mentioning ‘carnal lances’, unaccompanied by reference to ‘bollock-hafted daggers’ (though sometimes they are accompanied by a reference to ‘stones’, strongly suggesting testicles).[5] An indictment which mentions the ‘bollock-hafted dagger’ alone, and which discloses that the allegation is one of sexual violation, can be seen in a 1454 file. This states that a certain William Shepley, tailor, on 31st October 1453, broke into Henry Smith’s house near Campsall, Yorkshire, stole some items, and raped Henry’s wife, Agnes, ‘with force and arms, i.e. with a … ballokhafted dagger’, penetrating her ‘secrets’.[6] This does all seem to make a good case for saying that both ‘carnal lances’ and ‘bollock-hafted daggers’ were meant to be understood as penises. Further support might be derived from the additional details in the Shepley record: it notes that William’s ‘bollock-hafted dagger’: is ‘a large instrument of very little value’, putting that low value at one penny (much lower than the values assigned to most real weapons of the time),[7] and elaborating on the length of the ‘instrument’. We might wonder whether it is conceivable that the allegation is one of violation with a real knife, but there is no sign that violation with an object would have been labelled raptus in medieval England. Those familiar with literary history will be aware of the long tradition of imagery centring on fighting and weapons, in connection with sex and with male genitals: medieval people were likely to have been used to this switching back and forth between body part and weapon, in the sexual context.[8]

We cannot be sure by what route this imagery came to be included in the record: was it a transcription of the initial accusation, or an elaboration by the clerk who recorded it? We can be sure, though, that it was a choice: most medieval rape or sexual offence entries do not include such material, so clearly it was not a requirement. If it had no formal function, though, why include it? Highly questionable as it seems to us, these accounts of ‘carnal lances’,‘bollock-hafted daggers’ and ‘large instruments’ were probably included in the record because they were considered humorous. Discussion of penis size and quality, as well as the connection between penis and suggestive dagger form, in the context of sexual offences, would certainly seem to have something in common with the tone of some of the ‘jokes’ about women, sex and rape seen in the clubby, men-only conversations reportedly carried on by serjeants and judges at Westminster, and passed down to legal posterity, in the Year Books.[9]

What more does the inclusion of this inessential material tell us about attitudes to the accused men? Although we may detect some ridicule of the defendant in the ‘low value’ part of the 1454 description, the ‘large instrument’ is presumably not similarly negative, and, taken overall, the use of the ‘penis-as-weapon’ image is not likely to have been damaging to an alleged offender; perhaps quite the reverse. In a world in which even socially-acceptable sex was seen as something a man did to a woman, in which a degree of male aggression was expected,[10] which knew ‘playful’ combat imagery in discussions of sex, and in which men carried real and aggressively suggestive ‘bollock-hafted daggers’, an image of unlawful sex as wounding with a weapon would be far less damning of the alleged perpetrator than it now appears.

Some of the ideas incorporated in these records are certainly offensive from the point of view of the modern scholar, but they may also be illuminating, in the quest to understand the mental world of medieval men, and the attitudes faced by medieval women in their encounters with the legal system. Much scholarly attention has been paid to the interpretation of entries relating to raptus, and whether or not particular allegations so designated concerned rape as we would understand it today, but cases such as that of Thomas Hervy, with which I began should alert us to the possibility that there are also cases not labelled raptus, which may, in fact, have involved allegations of sexual misconduct. Beyond that, though the number of cases which mention these suggestive weapons seems, thus far, to be small, the insights they can provide for our understanding of the interplay between wider culture and legal proceedings, in this difficult and important context, may prove to be of more than minimal value.[11]

Gwen Seabourne

11th May, 2024.

[1] KB 27/697 Rex m.5. All linked scans are from AALT.

[2] See, in particular, S.F.C. Milsom, ‘Trespass from Henry III to Edward III,’ Law Quarterly Review 74 (1958), 195-224; 407-436; 561-590.

[3] In this instance, the suggestion is that this was with some degree of consent on her part.

[4] See Ole-Magne Nøttveit, ‘The kidney dagger as a symbol of masculine identity – the ballock dagger in the Scandinavian context’, Norwegian Archaeological Review 39 (2006), 138-50. Note that the dagger’s ‘bollocks’ were renamed as kidneys by nineteenth century-antiquarians.

[5] See, e.g.: KB 9/359/mm. 67, 68; KB9/363 m. 2; KB 9/363 m.3 Sometimes there is additional information linking the lance to penetration of a woman’s body: see, e.g. KB 27/725 m. 31d For the stones-testicles link, see, e.g., W.J. Whittaker (ed.), Mirror of Justices (London: B. Quaritch, 1895), book I c. 9.

[7] The offence was committed ‘[cum] … magne instrumento minime valoris’. For the use of instrumentum for the penis, see Dictionary of Medieval Latin from British Sources (Brepols, 2018), s.v. ‘instrumentum’, 6c.

[8] See, e.g., D. Izdebska, ‘Metaphors of weapons and armour through time’, in W. Anderson, E. Bramwell, C. Hough, Mapping English Metaphor Through Time (Oxford, 2016), c. 14; Robert Clark ‘Jousting without a lance’, in F.C. Sautman and P. Sheingorn (eds), Same Sex Love and Desire Am407-436ong Women in the Middle Ages (New York, 2001), 143-77, 166; Dictionary of Medieval Latin from British Sources, s.v. ‘hasta’, 6.

[9] See, e.g., G. Seabourne, ‘Et Subridet etc.’: smiles, laughter and levity in the medieval Year Books. In T. Baker (ed.), Law and Society in Later Medieval England and Ireland: Essays in honour of Paul Brand (London: Routledge, 2018), 201-224, which you can see here. See also the contention that the inclusion of a particularly detailed fourteenth century rape case in medieval lawyers’ instructional manuscripts indicates that it was seen as having ‘titillatory’ value: B.A. Hanawalt, ‘Whose story was this? Rape narratives in medieval English courts’, in her ‘Of Good and Ill Repute’: gender and social control in medieval England (Oxford University Press: New York, 1998), 124-141.

[10] See, e.g., R. Mazo Karras and K. Pierpont, Sexuality in Medieval Europe: Doing Unto Others, 4th edn, (Routledge: London, 2017).

[11] There is a copious literature on the medieval literature of sexual misconduct. For those new to it, S. McSheffrey and J. Pope, ‘Ravishment, legal narratives, and chivalric culture in fifteenth-century England’, Journal of British Studies 48 (2009), 818-836, and references therein, would be a good entry point.