It is a wet morning and I am stuck indoors, an arm stiff from a Covid jab: not up to doing anything terribly energetic, but in need of some distraction. Naturally enough, I have turned to reading about some favourite topics – law, humour and poetry (loosely so-called). All of them come together in this report of goings-on in a county court in Cardiff, in 1907: Lloyd Meyrick, ‘Limericks and Law’. It alludes to the occasion, on 8th May 1907, when a judge, William Stevenson Owen, at Cardiff County Court, brightened up a dullish case by breaking out into a limerick.

This tale contributes to the image of this particular judge as something of a funny fellow. Newspapers of the period could not get enough of his ‘humorous’ remarks and caustic quips. Meyrick noted that, in court, Owen elicited laughter, ‘weak cackles and short hysterical yelps’, that he was known as one for ‘polished periods and sparkling epigrams’, but it was only at that point that he had revealed an ‘unsuspected vein of poetry’.

Mentioned in passing in this report were limericks about ‘A young lady from Chichester’ and another young lady, this time from Exeter, but Meyrick did not give the verses themselves. I had a bit of a search for possibles and found some rather rude ones.[i] (At least there was no hint of people hailing from Nantucket. If you don’t know, use your imagination). But, perhaps not surprisingly, there was no serious rudeness in Judge Owen’s court.

Luckily, the judge’s own limerick was reproduced in other, anonymous, reports, from 8th May 1907. Here it is in all its glory:

There was a young woman of Chichester

who went to see a solicitor.

He asked for his fee,

she said “Fiddle-de-dee:

I simply called as a visitor”.

Have to say the rhymes are a bit dodgy, but, according to the ‘stage directions’ in the newspaper report, the response in court was loud laughter. The newspaper report does not really explain what the nature of the case was, but it does seem likely to have involved an issue of whether somebody was consulting a solicitor professionally or not. Did he make it up there and then (in which case some struggling rhymes would be forgiven), or did he sit up for hours the night before, composing and polishing it (in which case, they would not)? In any case, it all adds to the picture of power-dynamics in court at this point, and, so it seems to me at least, the self-regard of judges.

I have quite a collection of judicial ‘humour in court’ reports now, and also a fair bit of material on Owen, who does seem worth investigating further.

Working from the newspaper archive (the easiest place to start!), the Welsh newspaper obituaries[ii] give us these apparent facts about his life:

1834 Born (1st February). Son of William Owen, of Withybush, Pembrokeshire (deceased), from a ‘well-known and highly-respected family in the county’.

?date Married to Miss Ray, Kent family, had three daughters and a son.

1856 Called to the Bar 1856. Became a Chancery barrister. Travelled the South Wales Circuit. ‘An accurate lawyer and a skilled equity draftsman’.[iii]

1883 Appointed County Court Judge in Mid-Wales

1884 Transferred to ‘Circuit No. 58’ (County courts at Cardiff, Newport, Barry, Chepstow, Abergavenny, Tredegar, Pontypool, Monmouth, Ross, Crickhowell and Usk.

1895 Chair of Pembrokeshire Quarter Sessions. Chair of Haverfordwest Quarter Sessions. Retired 1907.

1909 Died (4.30 a.m., 20th October) , at home in Abergavenny, Ty Gwyn, after an operation on ‘an internal complaint’.

1909 23rd October. Funeral, parish church, Llantilio Pertholey, nr Abergavenny. Grave on south side of church.

At the time of his death, he sat on the County Court Bench.

His legal views

Obituaries[iv] emphasise some detailed, technical views:

- opposition to the judgment summons system (on the grounds that it encouraged credit)

- support for a reduction in the time allowed for the collection of debt under Statute of Limitations, from 6 to 2 years.

His character or characterisation: ‘dry humour’ and ‘caustic and scathing observations’

In death, he was called a man ‘of strong character and striking individuality’,[v] and, in private life, ‘a charming host and a man of warm-hearted disposition’. [vi]

it was commented that he was ‘noted for the dry humour which he introduced into the prosaic proceedings of the county court’, and that ‘his smart, laconic commentaries frequently provoked laughter’. On the other hand, his ‘caustic and scathing observations … were things to be dreaded, as many a solicitor [would] admit’.[vii] There is a lot to interrogate there – both in terms of the apparent nature of his ‘dry humour’, and also the slightly sniffy suggestion that the proceedings of the county court were ‘prosaic’. My initial reading suggests that he was very keen to play up the importance of this, apparently scorned, jurisdiction. More on that in due course!

Obituaries noted the speed with which he picked up common law, that his judgments were rarely upset on appeal, that he was very fair to prisoners, in Quarter Sessions, and, in the County Court, ‘very much alive to the processes of the court being used to oppress the poor’, with particular attention to claims made by tallymen and moneylenders, and not to ask too much of poor defendants in terms of paying debts. Much, much more to say, I am sure, once I can delve further into his cases and the reports.

I note that the obituaries do not mention his poetical efforts. They do say that he had a ‘distinguished career’.[viii] That was clearly in law rather than literature, though.

GS

24/10/2022

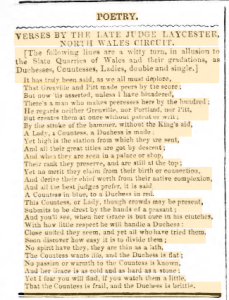

Image from The Evening Express, 20th October, 1909.

[i] Chichester:

A pious young lady of Chichester

made all of the saints in their niches stir

and each morning at matin

her breast in pink satin

made the bishop of Chichester’s britches stir

(shame about the double use of stir, to my mind, but Chichester/britches stir is rather skilful).

Exeter:

There was a young lady from Exeter,

So pretty that men craned their necks at her.

One was even so brave

As to take out and wave

The distinguishing mark of his sex at her.

(grim and creepy, obviously).

No refs to author, nor date, given.

Just how the Exeter verse mentioned by Meyrick was thought to end, we can’t be sure, but the first two lines were not quite the same as the rude version above – it began ‘There was a young woman from Exeter/ and a happy young man sat next to her’ [needs another syllable, doesn’t it ‘Sat down next to her’?]

[ii] See, e.g., ,. DEATH OF JUDGE OWEN.|1909-10-22|The Cambrian – Welsh Newspapers (library.wales) JUDGE OWEN DEAD|1909-10-20|Evening Express – Welsh Newspapers (library.wales) DEATH OF JUDGE OWEN.|1909-10-29|The Welshman – Welsh Newspapers (library.wales)

[iii] DEATH OF JUDGE OWEN.|1909-10-29|The Welshman – Welsh Newspapers (library.wales)

[iv] ,. DEATH OF JUDGE OWEN.|1909-10-22|The Cambrian – Welsh Newspapers (library.wales)

[v] DEATH OF JUDGE OWEN.|1909-10-29|The Welshman – Welsh Newspapers (library.wales)

[vi] DEATH OF JUDGE OWEN.|1909-10-29|The Welshman – Welsh Newspapers (library.wales)

[vii] ,. DEATH OF JUDGE OWEN.|1909-10-22|The Cambrian – Welsh Newspapers (library.wales)

[viii] JUDGE OWEN DEAD|1909-10-20|Evening Express – Welsh Newspapers (library.wales)