Here’s a colourful tale from fourteenth century Devon, showing an apparent scheme to fleece the locals using exotic claims to magic power, and playing on their greed.

The story comes out in the King’s Bench plea roll of Michaelmas term 1374, though it refers to events of quite some years earlier – in 1345, and a presentment before justices in Devon in 1354.[i] The tale was that Gervase Worthy, Geoffrey Ipswich and William Kele had come to the home of Rouland Smallcumbe at Barnstaple, and had spun a yarn to his wife. Their patter was that they were rather more exotic than the sort of people she was likely to have met, being converted pagans (pagani – I’ll have to look into just what that word signifies at this period, but it’s clearly some sort of ‘non-Christians’). Presumably as a result of their claimed questionable past religious status, they were believed when they claimed special powers: they could tell fortunes, including how long a person would live. They also said that they had other gifts, and worked on Rouland’s wife in such a way as to get her to believe that they could make precious items reproduce themselves. They got her to give them all her gold, silver and jewels, and other valuables. When she handed them over, Gervase convinced the gullible woman that he had put these in a chest, but in fact, it would seem using some sleight of hand and misdirection, he had made off with them. Getting her ‘invested’ in the magical process in a way modern magicians (or fraudsters) would appreciate, Gervase locked the chest, and took away the key, instructing Rouland’s wife that every day for nine days she should go to the church for three masses, and that she should not open the chest, When he returned, as he promised to do after that, with the key, her jewels, in the box, would have doubled! The rogues did not come back though, and the desperate woman broke open the chest. Sadly, she did not find the promised increased hoard, but a piece of cloth full of lead and (non-precious) stones. The presentment did not stop with this, however, but ascribed to the gang’s fraud another serious outcome: as a result of this deception, the woman became ill and soon died. It was also noted that the gang had made 200 marks across Devon by similar ruses. There does not seem to have been a conviction, however, and who knows whether there was any truth in any of this, but there is always something to take away from these unusual entries.

The elaborate ruse, with the idea that people (women in particular?) might be bamboozled by tales of exotic magic, says a lot about popular ideas of the existence of magic, but also its association with trickery. The combination of ‘pagan’ magic with Christian practices (note the masses), and the fact that the rogues claimed only to be former pagans – they were now safely Christian, so had the powers of the exotic pagan, but not the untrustworthiness – gives clues about ideas on non-Christians, and also their limitations. The idea of precious things breeding more precious things puts me in mind of usury (money breeding money – which was bad). And finally the idea that the poor woman’s death was thrown in as a bit of an afterthought – caused by the fraud in a sense, but not the main complaint – and the deceased never is named beyond the labelling as some absent man’s wife – is something of a comment on the place of women in the medieval common law, isn’t it? If only somebody would write a book about that …

GS

4/4/2021

[i] KB 27/455 Rex m.29 (AALT IMG 340). The earlier presentment is at JUST 1/198 m. 8 (IMG 3622).

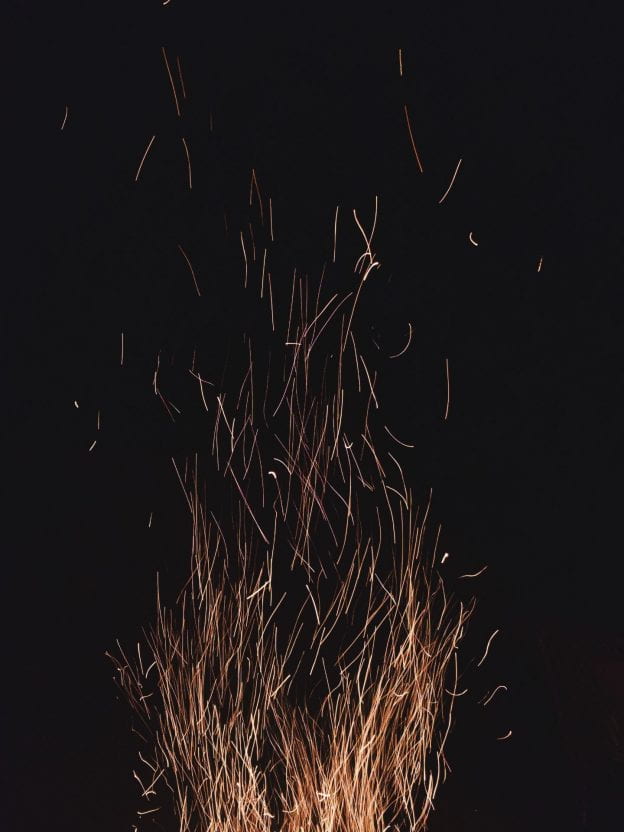

Photo by Roman Kraft on Unsplash